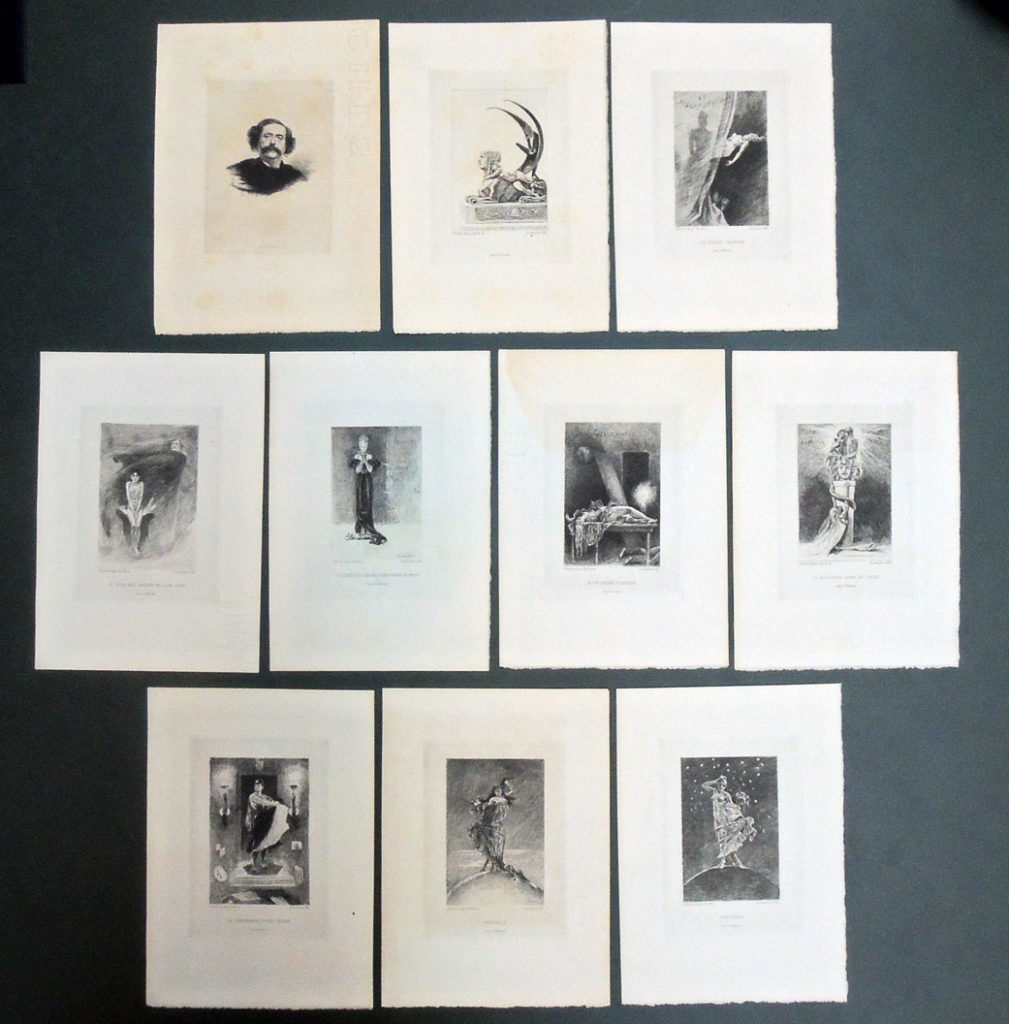

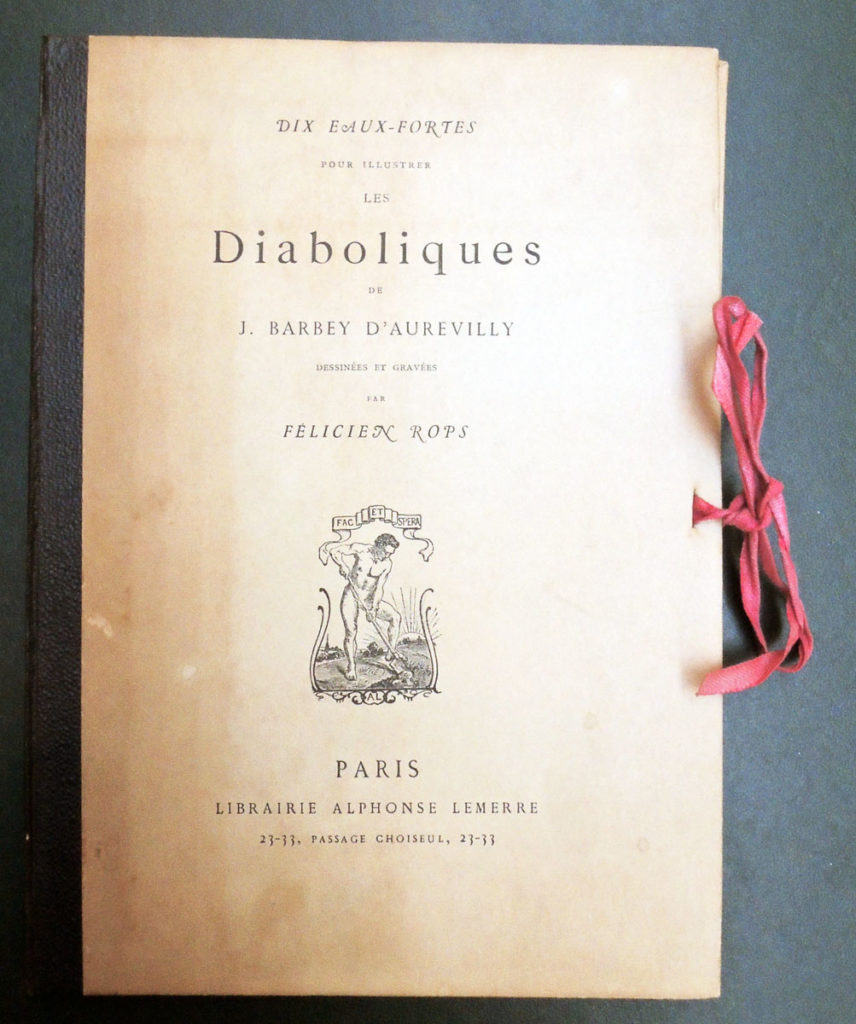

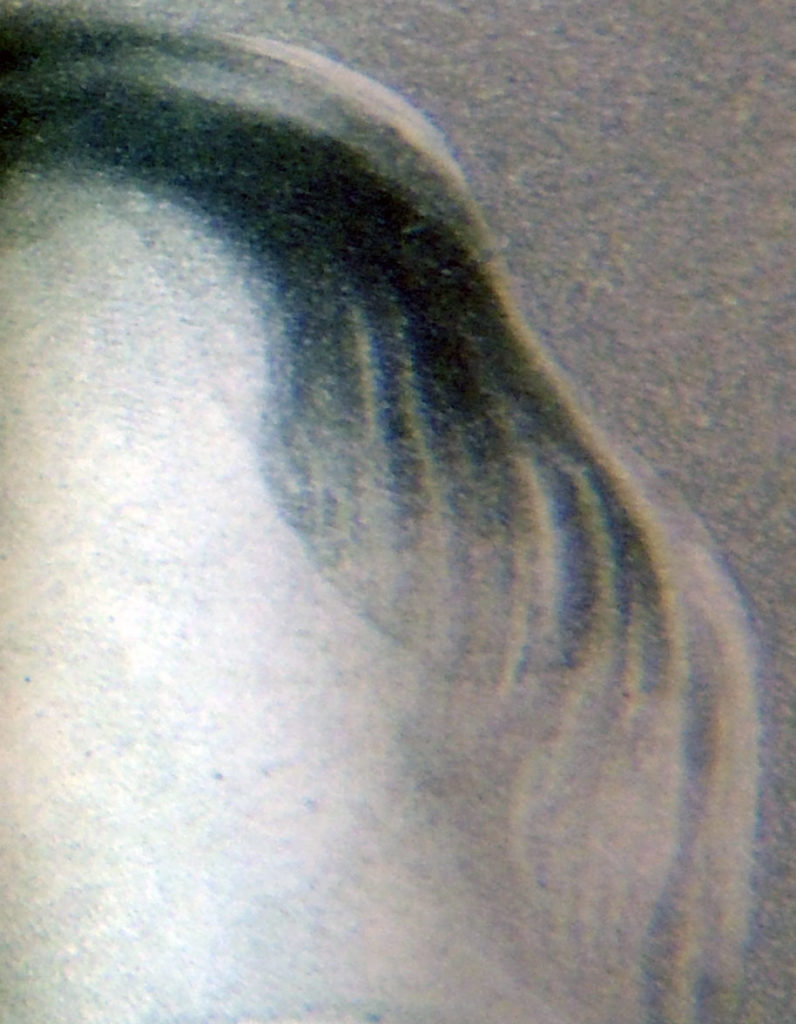

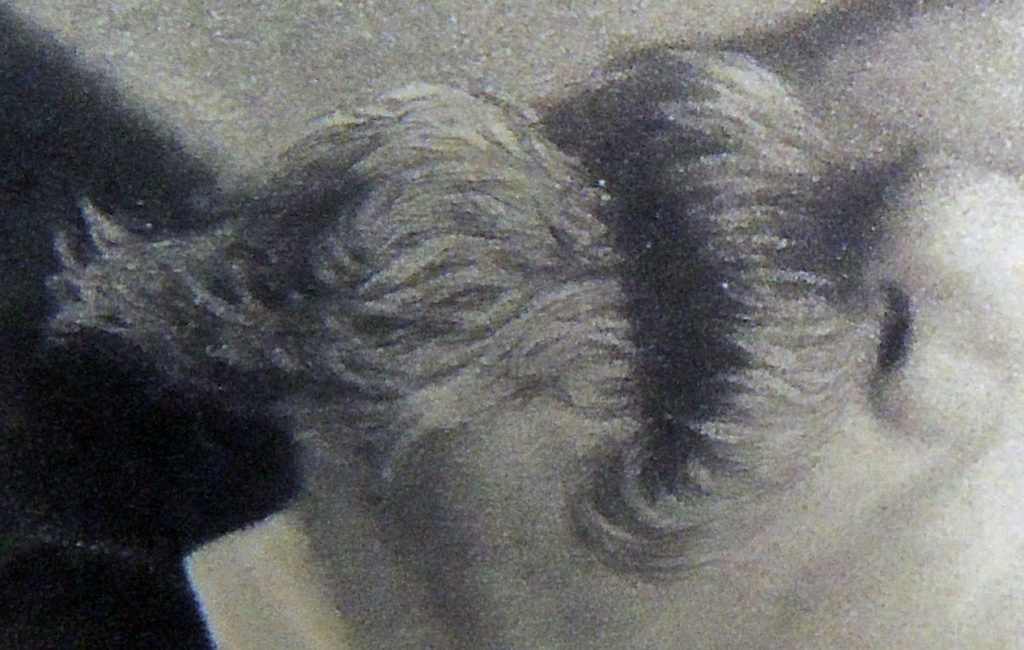

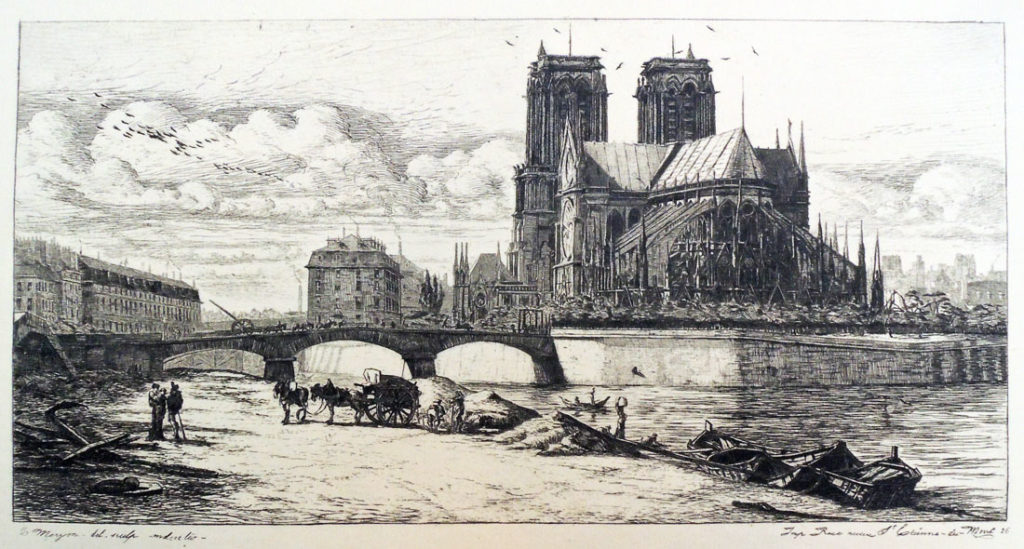

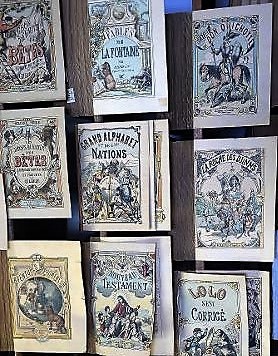

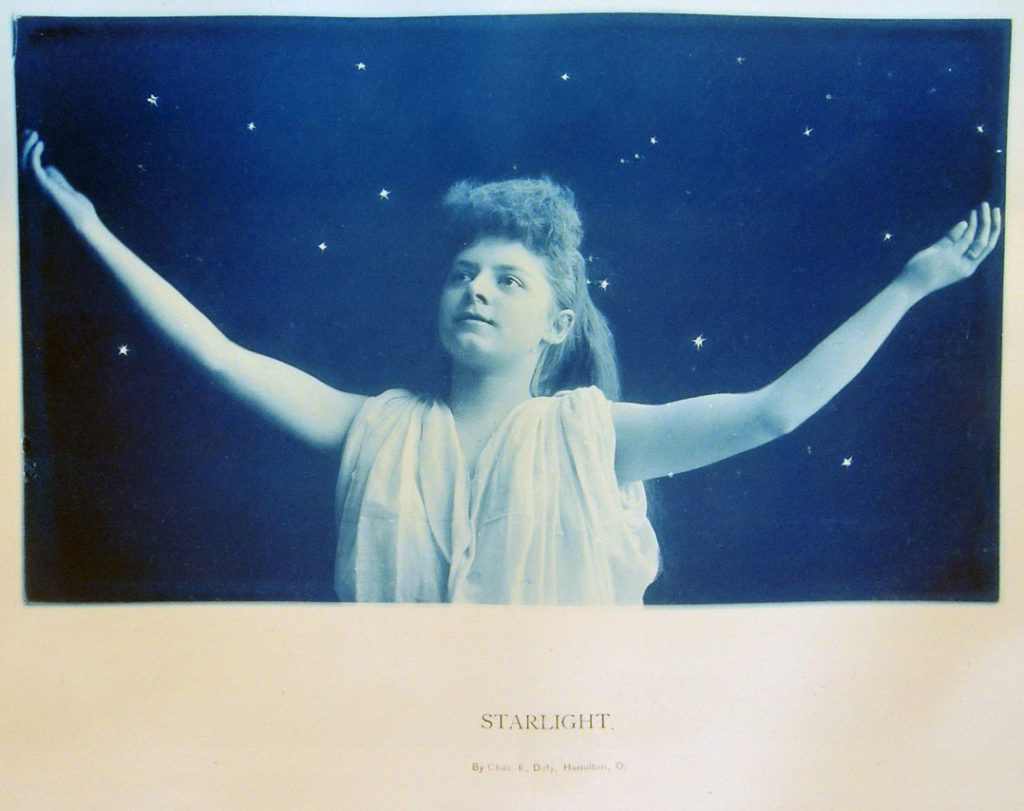

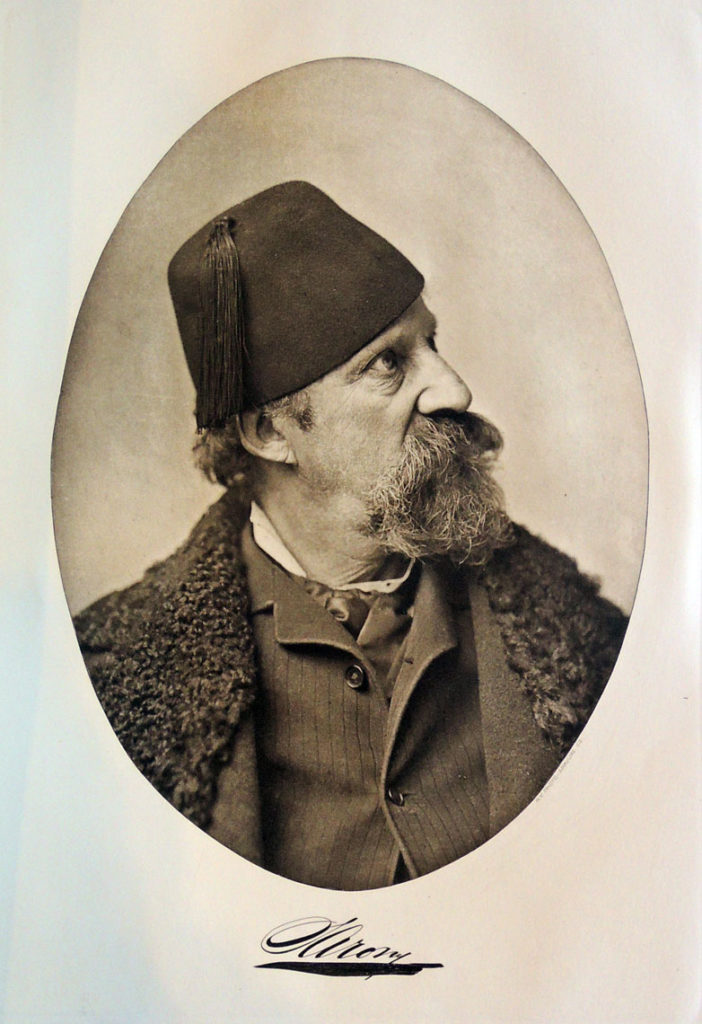

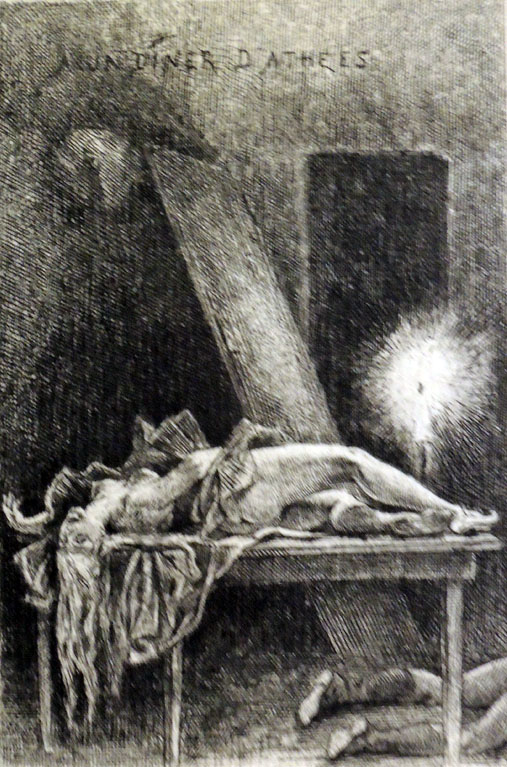

From his bookshop at Passage Choiseul, 23-33, Alphonse Lemerre (1838-1912) sold this portfolio of ten provocative prints for the 1874 short story collection Les Diaboliques by Jules Amédées Barbey d’Aurevilly (1808-1889). The prints are described on the title-page, and by bibliographer Erastène Ramiro, as etchings but except for the frontispiece (a portrait of the author engraved by Raul Rajon (1843-1888)), they are all photogravures with additional etching after drawings by the Belgian artist Felicien Rops (1833-1898).

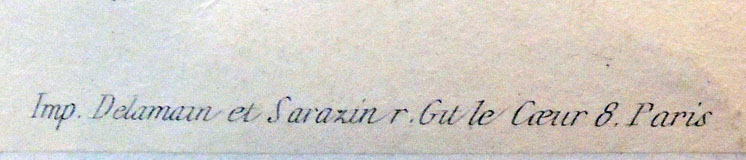

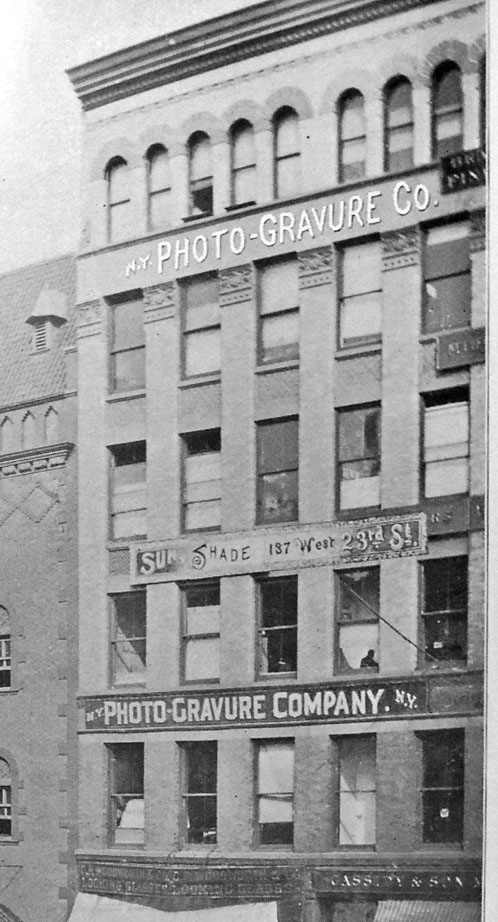

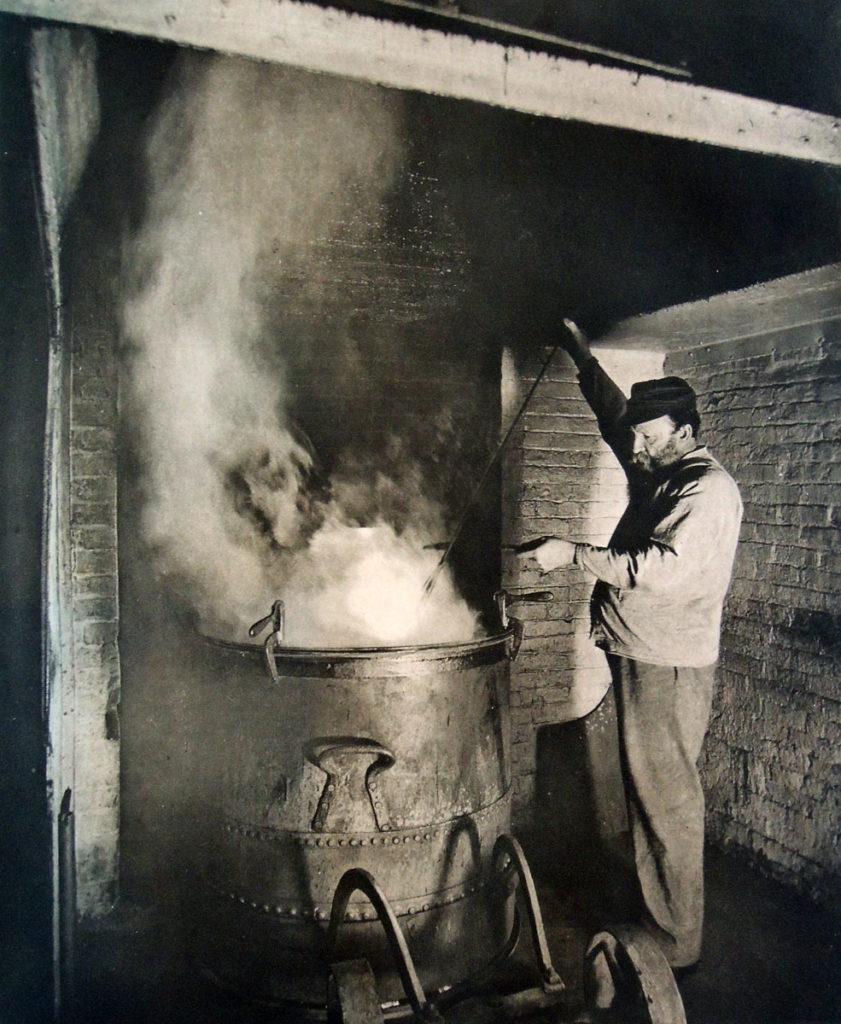

The copper plates were printed by Alfred Salmon (1825-ca. 1894), who was at this time in partnership with Adolphe Ardail (1835-1911), trading as Salmon & Ardail.

A second edition of Les Diaboliques was published in 1882 and these plates may have been for a third edition but no bound copy of the text with Rops’s plates is recorded. It is possible the project was never completed and so, the plates were issued separately. The nine Rops plates are Sphinx; Le Rideau Cramoisi; Le plus bel amour de Don Juan; Le dessous de cartes d’une partie de whist; A un diner d’athées; Le bonheur dans le crime; Le vengeance d’une femme; Postface; and Postface.

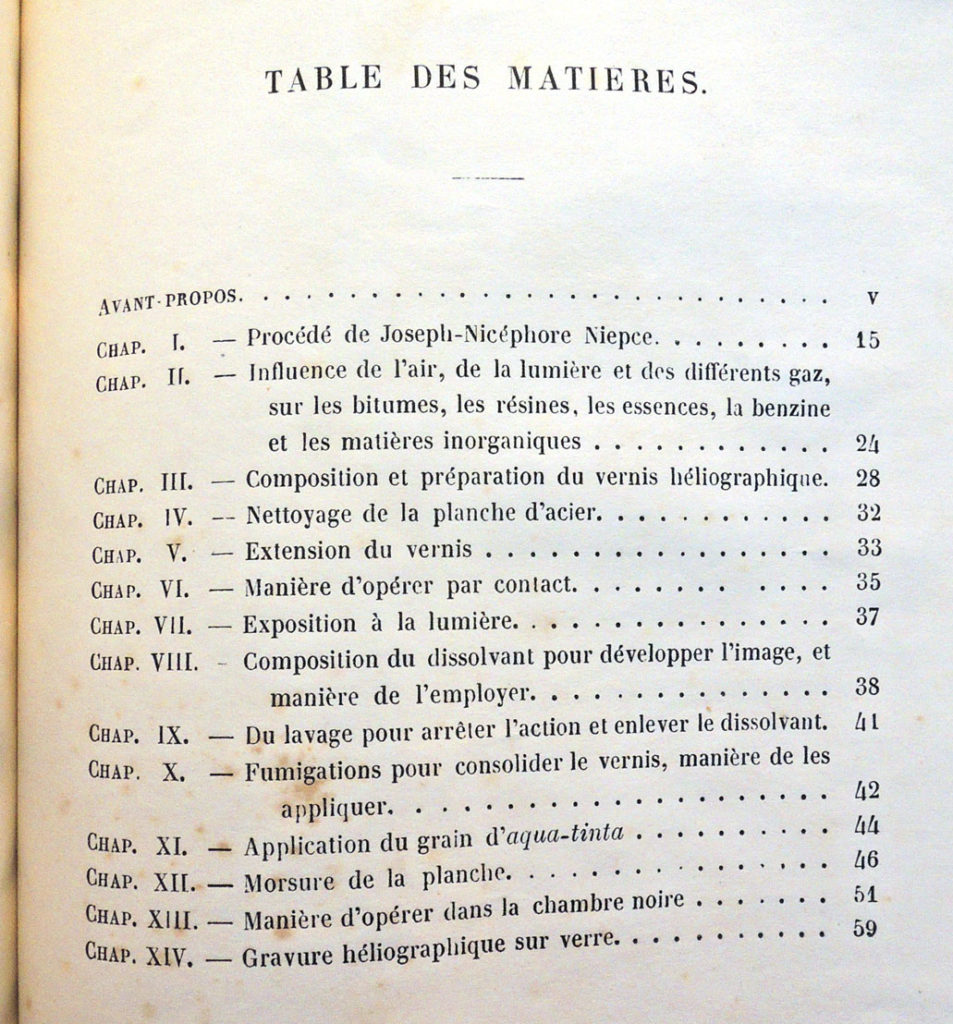

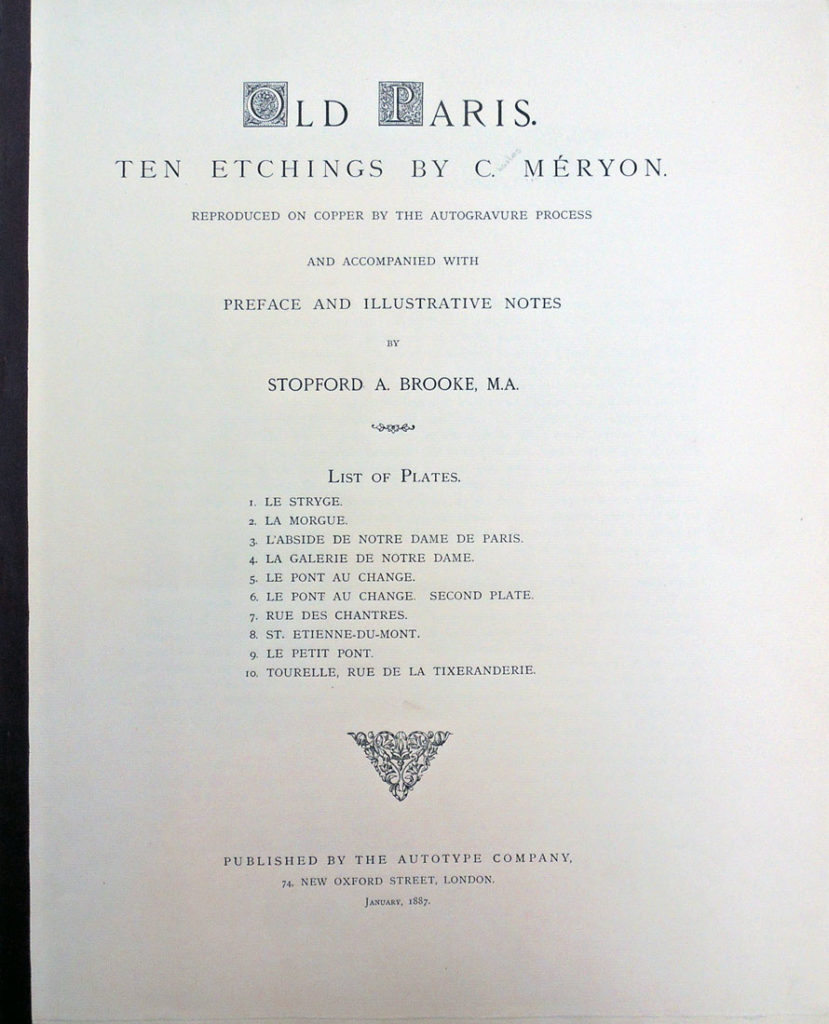

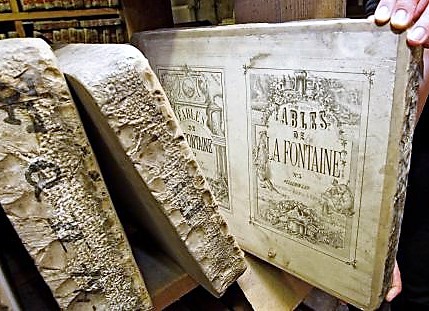

Félicien Rops (1833-1898), Dix eaux-fortes pour illustrer les diaboliques de J. Barbey D’Aurevilly; dessinèes et gravées par Félicien Rops ([Paris: A. Lemmerre, 1886]). One portfolio of ten etchings. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2018- in process

See also: Erastène Ramiro, Catalogue descriptif et analytique de l’œuvre gravé de Félicien Rops, précédé d’une notice biographique et critique par Erastène Ramiro; orné d’un frontispice et de gravures d’après des compositions inédites de Félicien Rops et de fleurons et culs-de-lampe d’après F. Rops, Jean La Palette et Louis Legrand (Paris: Librairie Conquet, 1887).