From left to right: Katarzyna (Kasia) Krzyzanska ’22, Marina Finley ’19, Ryan Ozminkowski ’19, Sergio De Iudicibus ’20, and Julia Ilhardt ’21.

From left to right: Katarzyna (Kasia) Krzyzanska ’22, Marina Finley ’19, Ryan Ozminkowski ’19, Sergio De Iudicibus ’20, and Julia Ilhardt ’21.

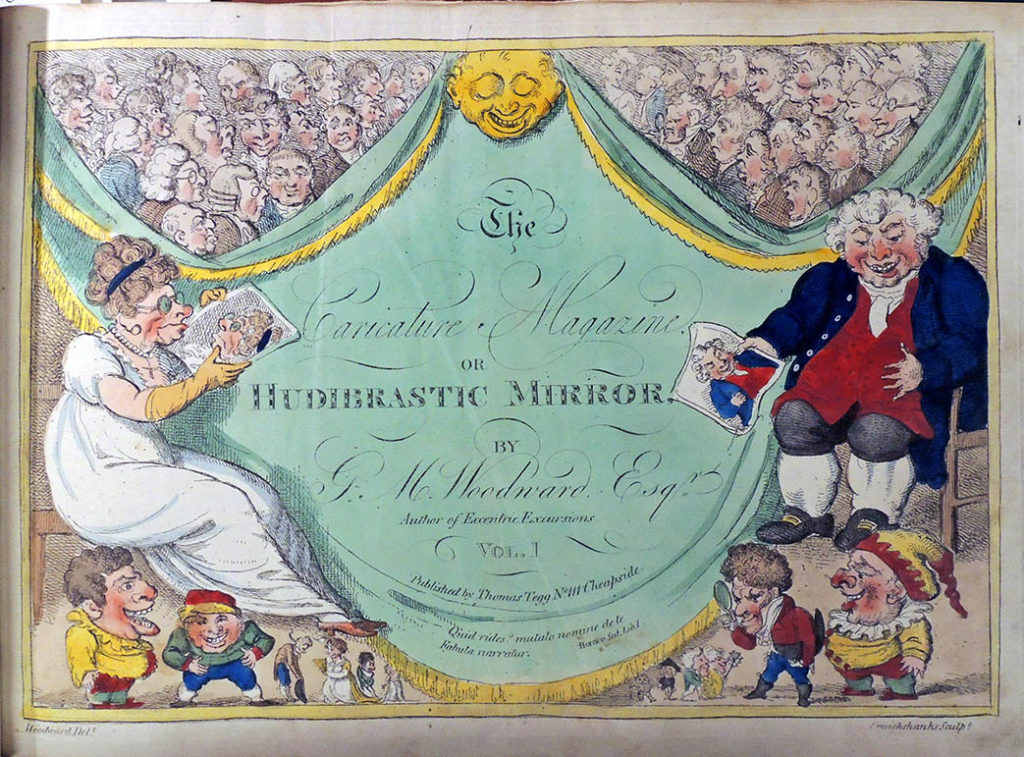

The Friends of the Princeton University Library gathered at Prospect House on Sunday, April 28 for their spring dinner and for the announcement of the winners of the 94th annual Elmer Adler Undergraduate Book Collecting Prize.

Among this year’s submissions, the most noticeable feature is an unusually diverse range of subject and format that have fueled the youthful passion of budding collectors. In addition to regular books on various topics and genres, this year’s contest has also attracted collectors of miniature books, Blue ray movies, music box discs, vinyl records, and other types. The judging committee had great joy learning so much from this eclectic range of essays.

A second feature that emerges from these essays is how often collecting is about human relationship. Interwoven with their history of collecting “curios” is frequently a story about their treasured relationship with family members, shared memories, experiences, and interests with parents and grandparents, and friendship with like-minded peers and teachers.

The 94th Elmer Adler Undergraduate Book Collecting Prize is awarded to five student collectors this year for their essays that, in the opinion of the judges, have “shown the most thought and ingenuity in assembling a thematically coherent collection of books, manuscripts, or other material normally collected by libraries.”

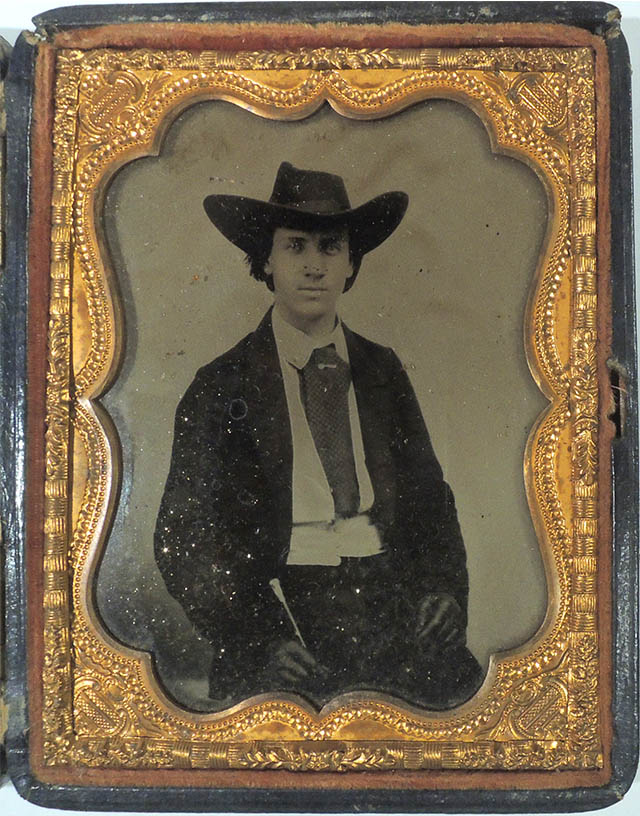

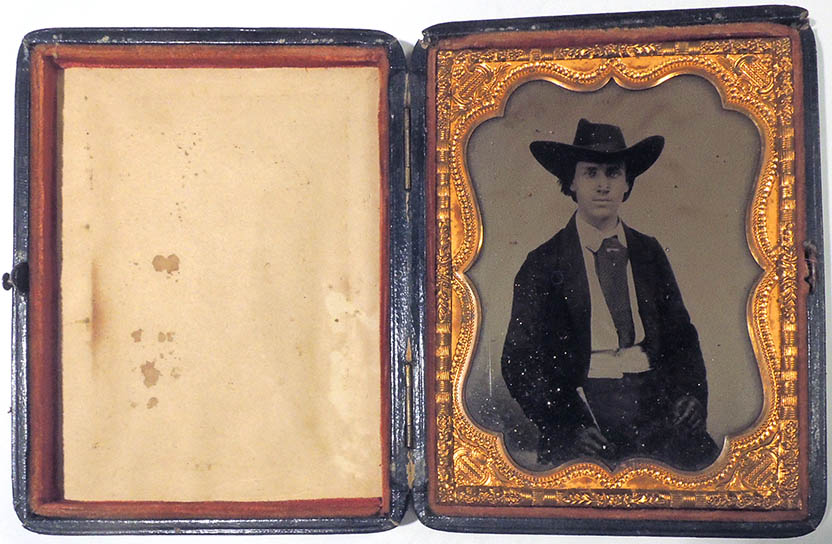

Congratulations to our first prize winner: Marina Finley, Class of 2019, for her essay “My Collection of Rubaiyats: A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread and 50 Extraordinary Books of Verse.” Marina curates a collection of diverse editions of the Rubaiyats of Omar Khayyam. The seed of the collection was a gift copy from Marina’s grandmother to grandfather in their adolescent years. The essay highlights twelve of the titles from her collection, bringing out their distinct features in such dimensions as style of illustrations, binding, size, shape, language, and country of publication. Marina’s essay will represent Princeton in the National Collegiate Book Collecting Contest organized by the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America.

Congratulations to our first prize winner: Marina Finley, Class of 2019, for her essay “My Collection of Rubaiyats: A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread and 50 Extraordinary Books of Verse.” Marina curates a collection of diverse editions of the Rubaiyats of Omar Khayyam. The seed of the collection was a gift copy from Marina’s grandmother to grandfather in their adolescent years. The essay highlights twelve of the titles from her collection, bringing out their distinct features in such dimensions as style of illustrations, binding, size, shape, language, and country of publication. Marina’s essay will represent Princeton in the National Collegiate Book Collecting Contest organized by the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America.

Marina is awarded $2,000 and a book donated by Princeton University Press to complement her collection: Music of a Distant Drum: Classical Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and Hebrew Poems translated by Bernard Lewis.

Second prize is awarded to Ryan Ozminkowski, Class of 2019, for his essay “I’m Blu Daba Dee Daba Die: A Story of Movies, Dreams, and Small Towns in California: A Blu Ray Collection.” Ryan curates a sizable Blu Ray movie collection, which started with a Christmas present when he was fourteen years old. His steadily expanding collection of Blu Ray discs has played a significant role in his Hollywood dreams, which Ryan pursues by engaging in movie making and gaining opportunities to work for Hollywood producers.

Second prize is awarded to Ryan Ozminkowski, Class of 2019, for his essay “I’m Blu Daba Dee Daba Die: A Story of Movies, Dreams, and Small Towns in California: A Blu Ray Collection.” Ryan curates a sizable Blu Ray movie collection, which started with a Christmas present when he was fourteen years old. His steadily expanding collection of Blu Ray discs has played a significant role in his Hollywood dreams, which Ryan pursues by engaging in movie making and gaining opportunities to work for Hollywood producers.

Ryan receives a prize of $1,500 and a copy of Hollywood Highbrow: From Entertainment to Art by Shyon Baumann.

There was a tie for third prize. Julia Ilhardt, Class of 2021, won with her essay “Records of the Past: A Music Box for the Ages.” Julia’s collection of music box discs began with an exquisitely crafted music box, gifted from her great-grandfather to her great-grandmother seven decades ago. Julia took over a collection of discs, which had been under the care of generations of women in her family, and continued to grow the collection. The discs embody shared experiences, memories, and tastes across generations.

There was a tie for third prize. Julia Ilhardt, Class of 2021, won with her essay “Records of the Past: A Music Box for the Ages.” Julia’s collection of music box discs began with an exquisitely crafted music box, gifted from her great-grandfather to her great-grandmother seven decades ago. Julia took over a collection of discs, which had been under the care of generations of women in her family, and continued to grow the collection. The discs embody shared experiences, memories, and tastes across generations.

Sergio De Iudicibus, Class of 2020, won with his essay “Riding a Rattling Soviet Bus: the Honesty of Forgotten Recordings.” Sergio has a passion for what he calls unorthodox music recordings which are not necessarily edited to the perfection but have captured the rawness of the occasion, allowing him to visualize the humans, instruments, and equipment by listening closely to the disembodied sound waves.

Both Julia and Sergio receive a prize of $1,000 and a book published by Princeton University Press. Julia is given a copy of Reflections on the Musical Mind: An Evolutionary Perspective by Jay Schulkin. Sergio is given Why You Hear What You Hear: An Experiential Approach to Sound, Music, and Psychoacoustics by Eric Heller.

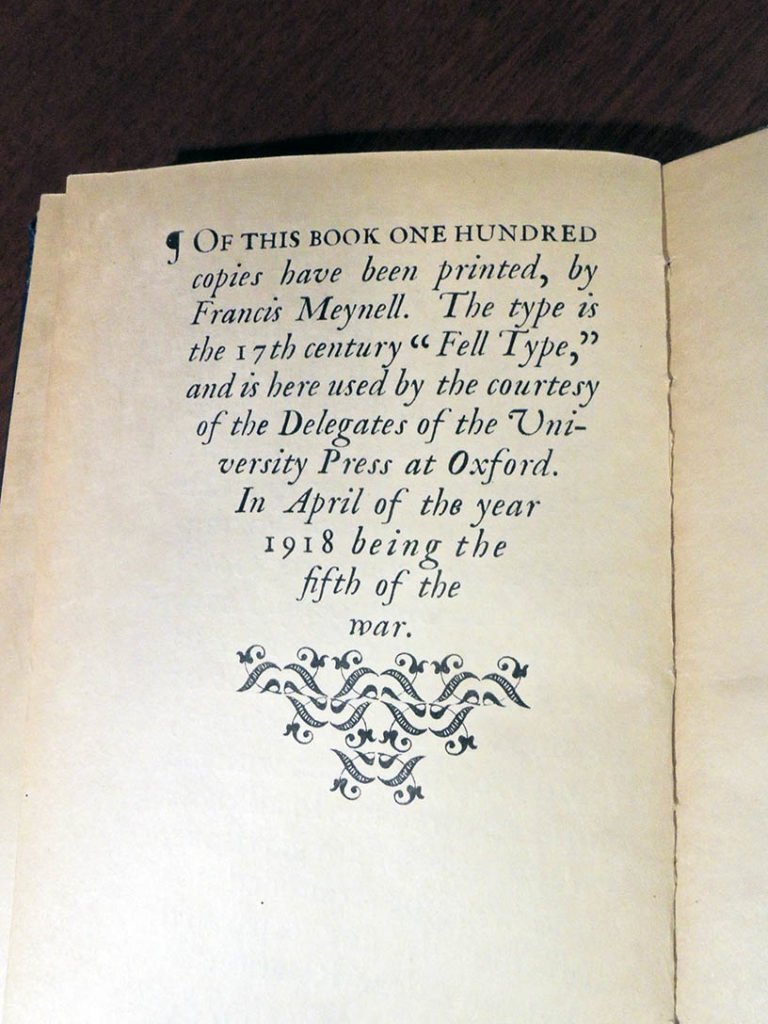

An honorable mention was awarded to Katarzyna (Kasia) Krzyzanska, Class of 2022. Kasia’s book collection has the distinct advantage of being portable. Her essay is not about ebooks on tablets though—the title is “A Library That Fits in a Suitcase: Collecting Miniature Books.” When she travels in the United States or in Poland, where her family came from, she searches for poetry anthologies, dictionaries, and classic works as small as a matchbox. Kasia prefers to discover them in brick-and-mortar stores than having such books conveniently shipped from online shops. As she wrote, the seemingly unnecessary fuss is part of the joyful experience that she seeks from collecting.

An honorable mention was awarded to Katarzyna (Kasia) Krzyzanska, Class of 2022. Kasia’s book collection has the distinct advantage of being portable. Her essay is not about ebooks on tablets though—the title is “A Library That Fits in a Suitcase: Collecting Miniature Books.” When she travels in the United States or in Poland, where her family came from, she searches for poetry anthologies, dictionaries, and classic works as small as a matchbox. Kasia prefers to discover them in brick-and-mortar stores than having such books conveniently shipped from online shops. As she wrote, the seemingly unnecessary fuss is part of the joyful experience that she seeks from collecting.

Kasia is awarded the book How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain by Leah Price.

All the winners also receive a certificate from the Dean.

Prizes were announced on Sunday by Minjie Chen, chair of the Adler Judging Committee and P. Randolph (Randy) Hill ’72, chair of the Friends of the Princeton University Library. Special thanks to this year’s fellow judges: Claire Jacobus (member of the Friends), Jessica Terekhov (Student Friends member), John Logan (Literature Bibliographer), Julie Mellby (Graphic Arts Curator), and Emma Sarconi (Reference Professional for Special Collections). Princeton University Press generously donated all the books awarded to students.

Congratulations to all the winners!

[Photography by Shelley Szwast]

While her brothers William and Cleveland attended Princeton University and then moved to New York City to work in the family business, Mary (May) Melissa Hoadley Dodge (1861-1934) chose to move away from the family, finally settling in England. As the daughter of William Earl Dodge, Jr. (1832-1903), the developer of the largest copper mining and copper wire manufacturing companies in America, May Dodge had significant funds at her disposal, which she used to sponsor many causes.

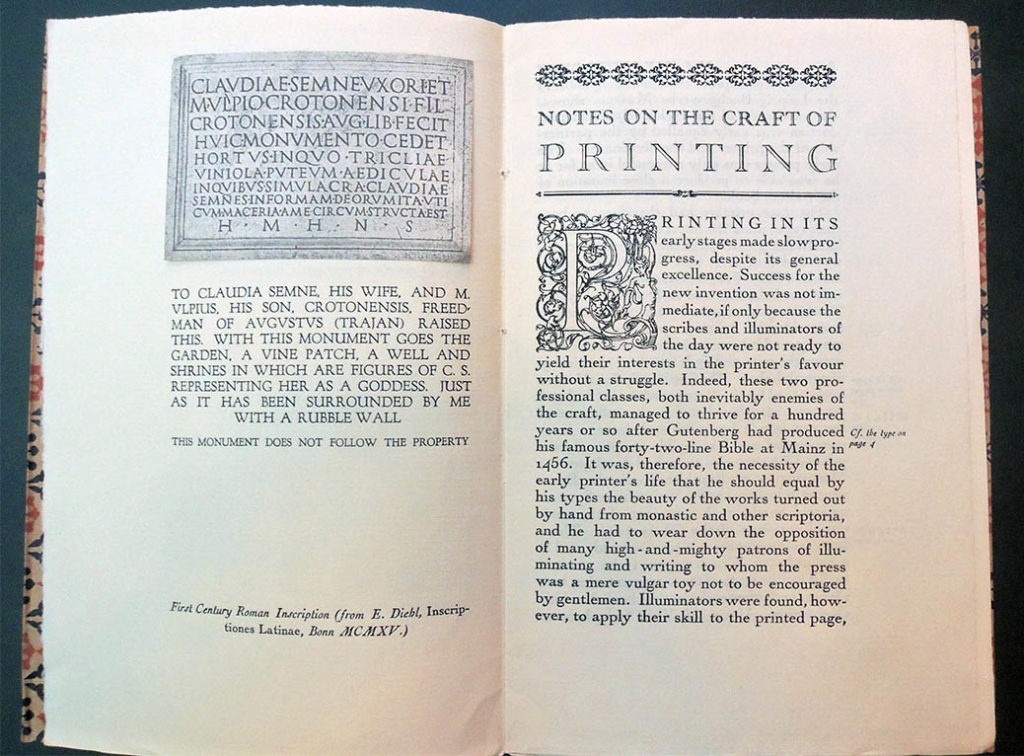

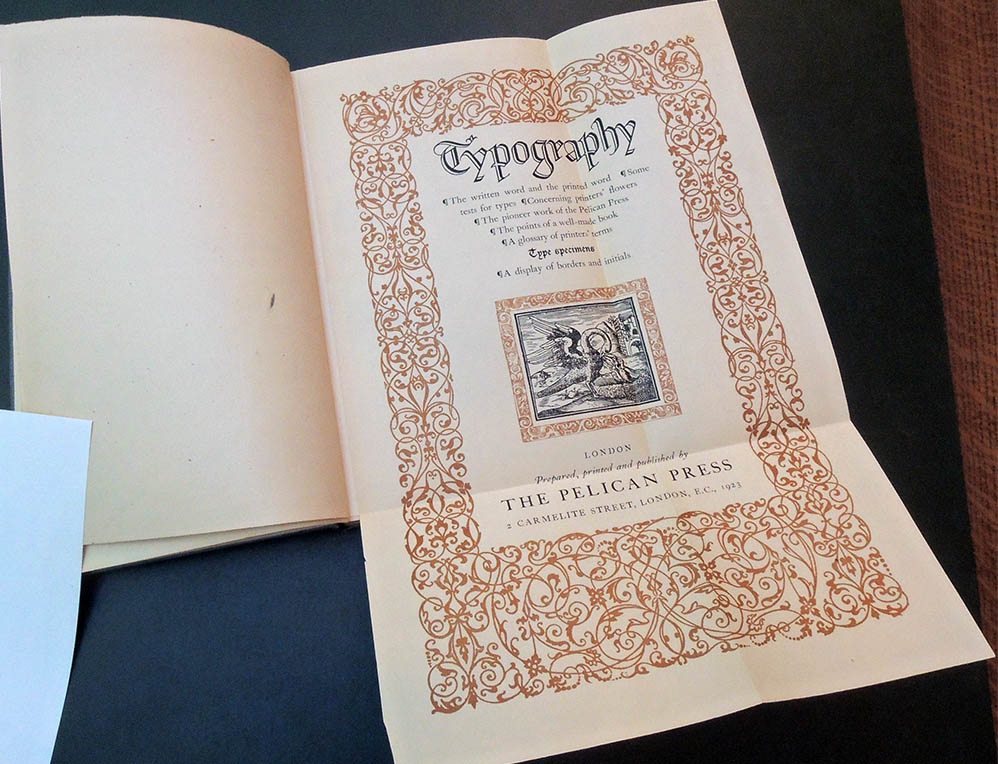

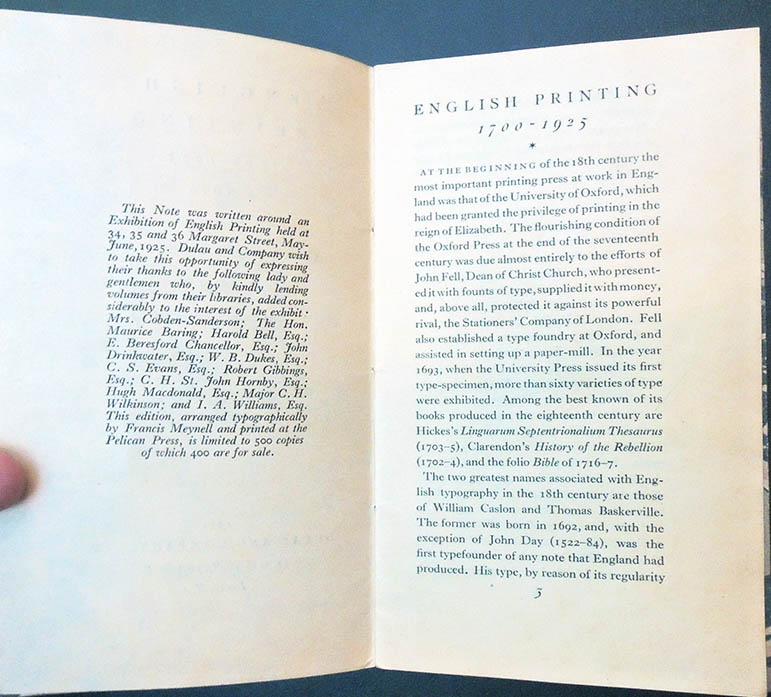

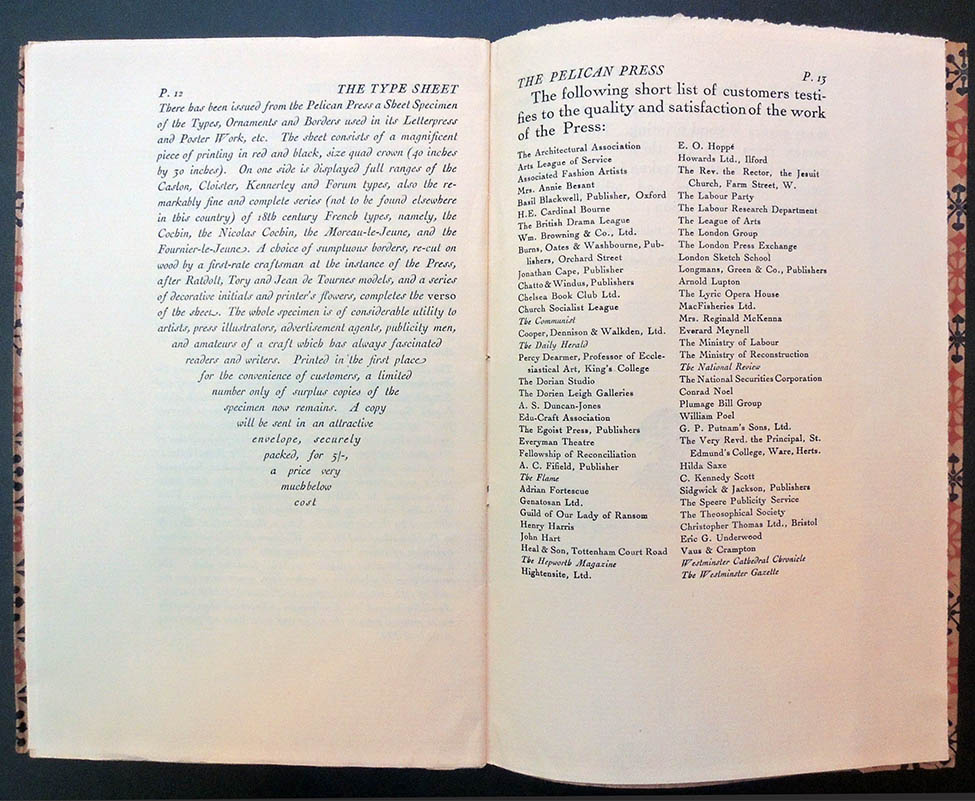

While her brothers William and Cleveland attended Princeton University and then moved to New York City to work in the family business, Mary (May) Melissa Hoadley Dodge (1861-1934) chose to move away from the family, finally settling in England. As the daughter of William Earl Dodge, Jr. (1832-1903), the developer of the largest copper mining and copper wire manufacturing companies in America, May Dodge had significant funds at her disposal, which she used to sponsor many causes. Together with her companion Countess Muriel De La Warr (1872-1930), May continued to support Meynell’s projects, supplying the capital to establish a new imprint, Pelican Press, in 1916. Even when he was fined £2,000 pounds for libel, after publishing a controversial cartoon of J.H. Thomas as Judas, Mary found a way to slip him the money to pay the fine.

Together with her companion Countess Muriel De La Warr (1872-1930), May continued to support Meynell’s projects, supplying the capital to establish a new imprint, Pelican Press, in 1916. Even when he was fined £2,000 pounds for libel, after publishing a controversial cartoon of J.H. Thomas as Judas, Mary found a way to slip him the money to pay the fine.