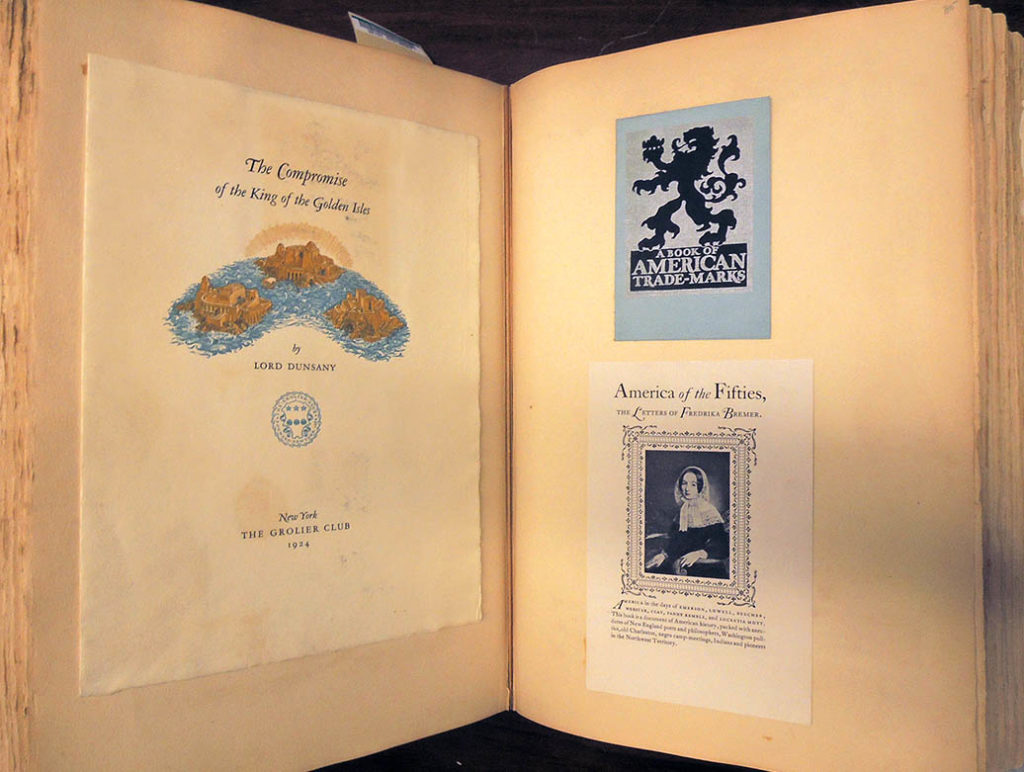

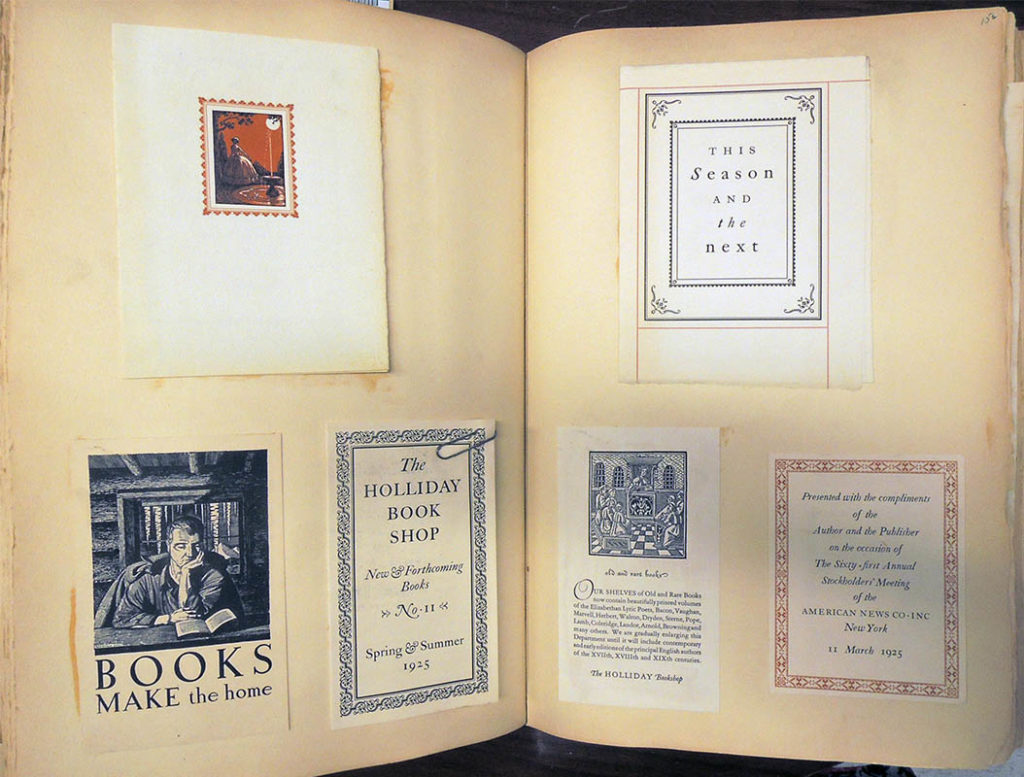

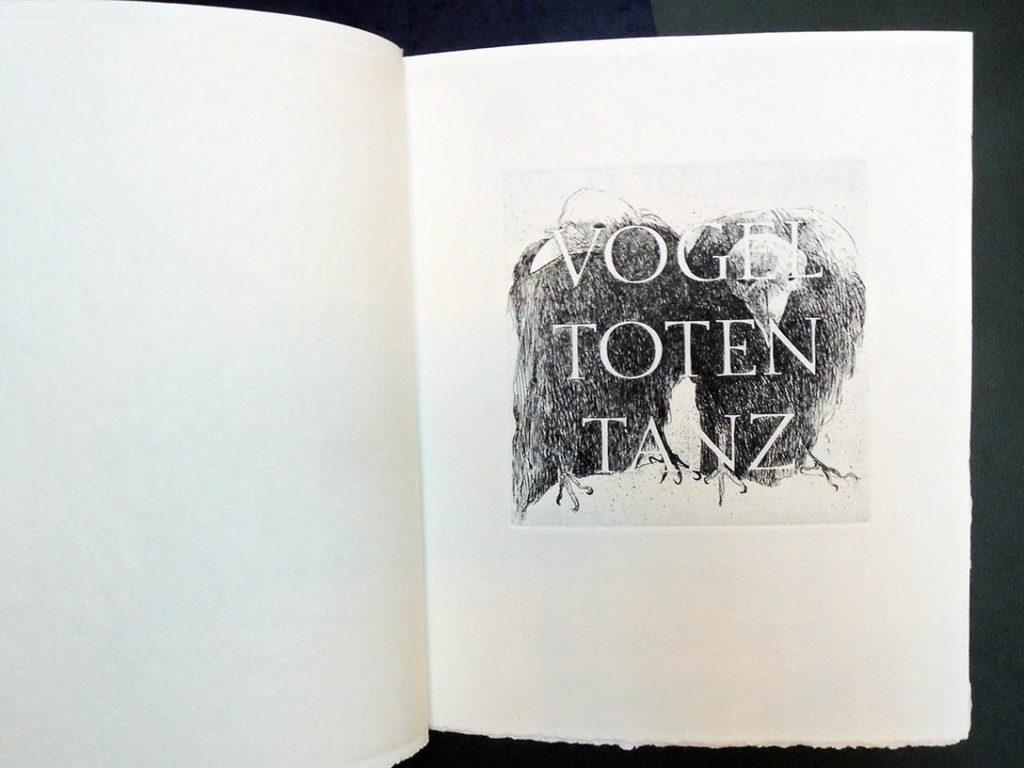

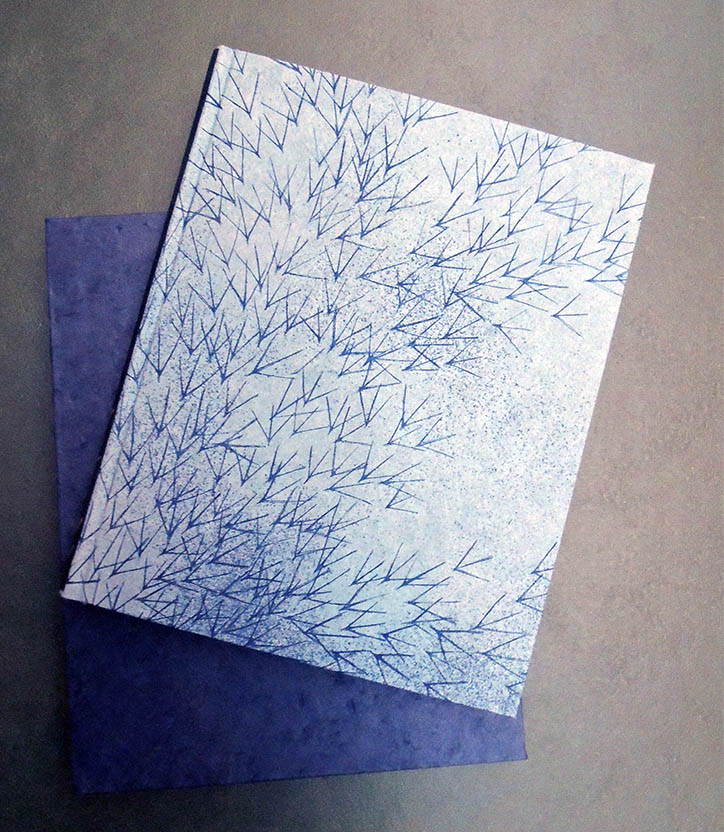

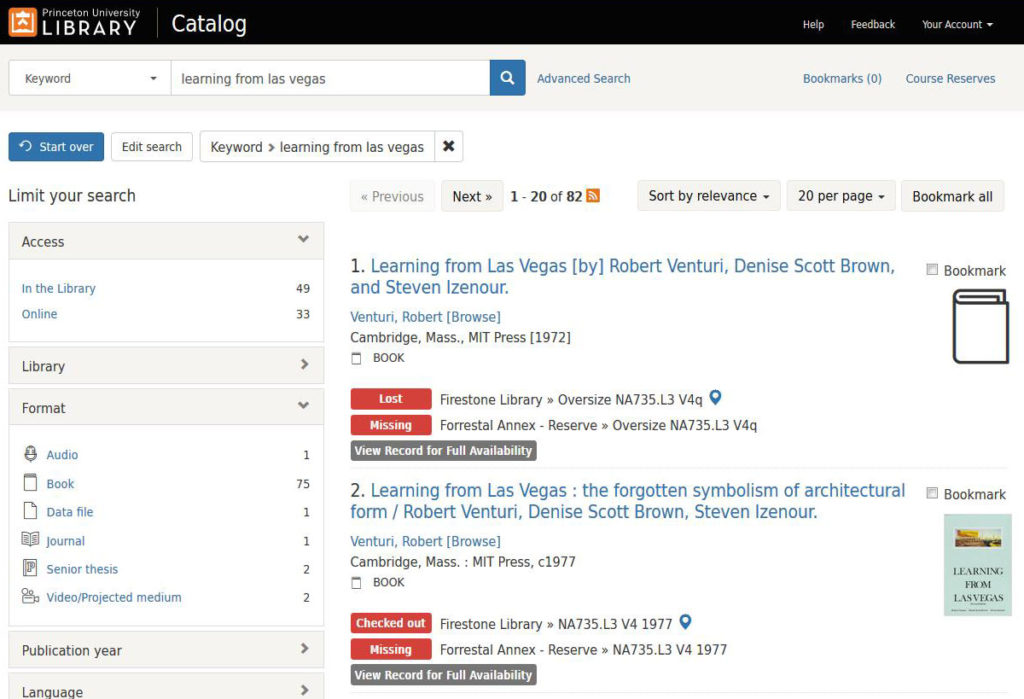

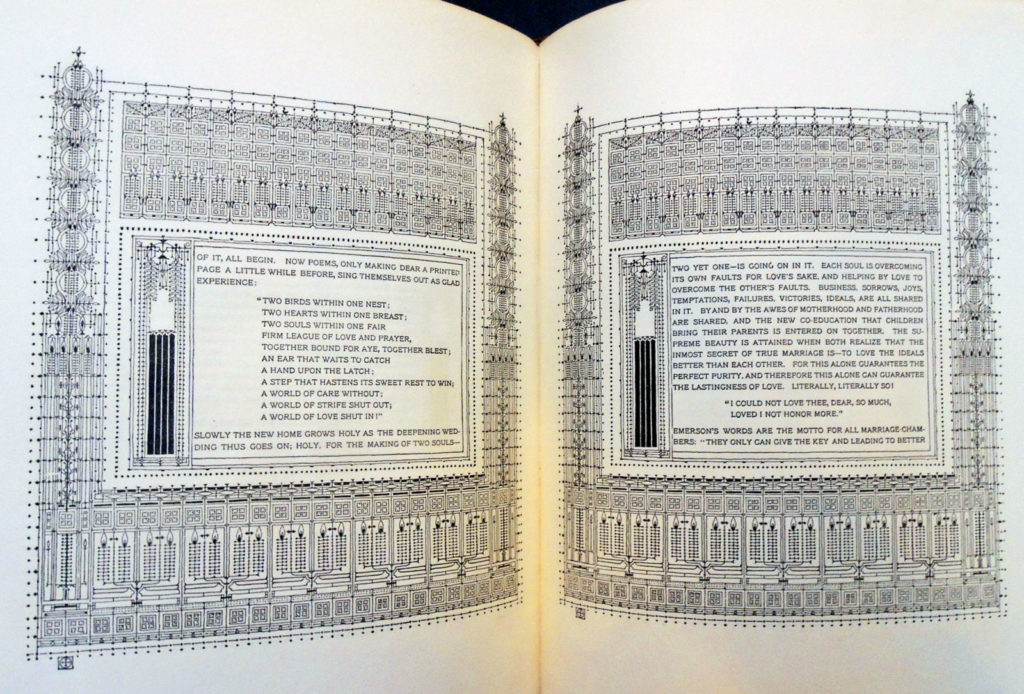

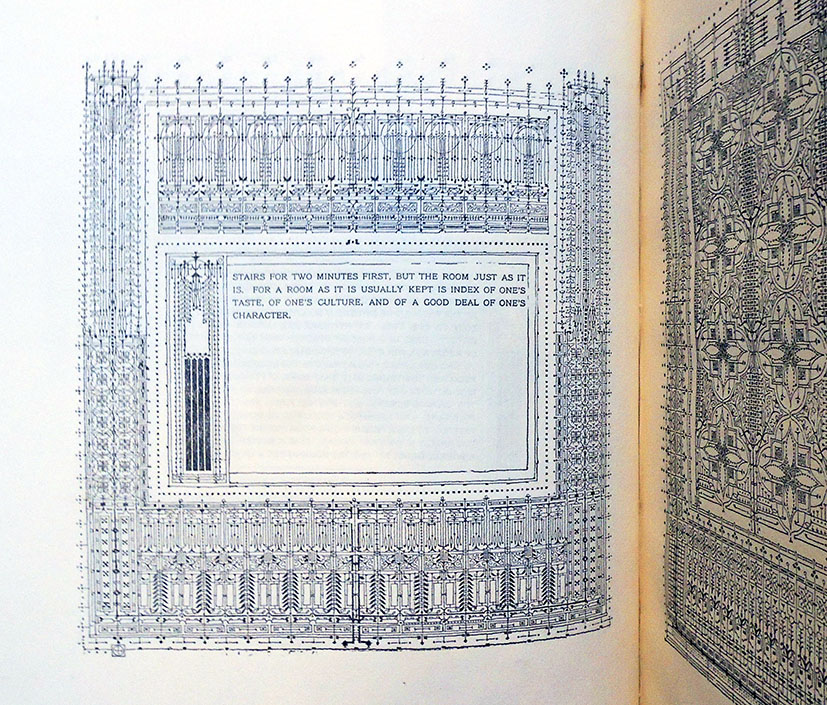

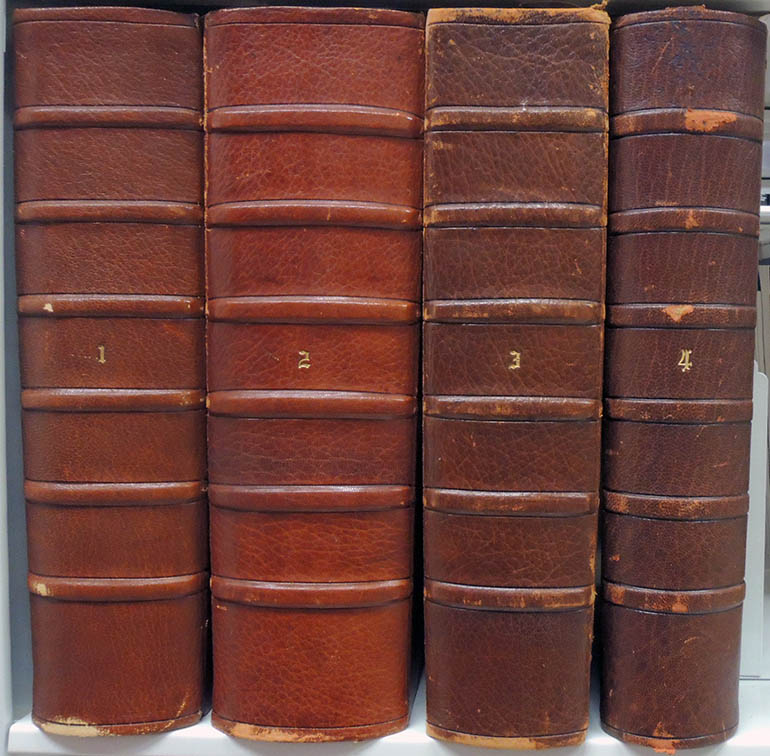

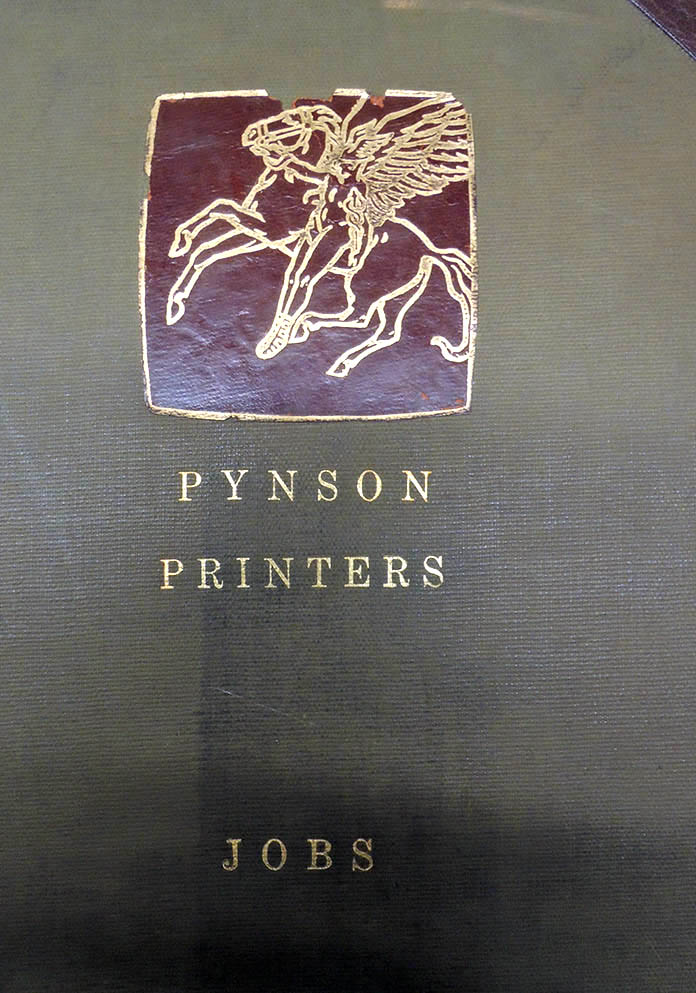

The Graphic Arts reference collection holds four enormous volumes documenting jobs produced by Elmer Adler’s Pynson Printers from 1922 to 1940 when the press was closed. An index to these volumes has been created by Sherry X. Zhang and Jena Mayer with help from Brianna R. Cregle and AnnaLee Pauls, which is key word searchable allowing researchers, for the first time, to study Adler’s commercial work. PDFs are attached here and to the voyager record for these scrapbooks. https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/7343684 Pynson Printers jobs. Graphic Arts: Reference Collection Oversize Z232.P99 A9f

The Graphic Arts reference collection holds four enormous volumes documenting jobs produced by Elmer Adler’s Pynson Printers from 1922 to 1940 when the press was closed. An index to these volumes has been created by Sherry X. Zhang and Jena Mayer with help from Brianna R. Cregle and AnnaLee Pauls, which is key word searchable allowing researchers, for the first time, to study Adler’s commercial work. PDFs are attached here and to the voyager record for these scrapbooks. https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/7343684 Pynson Printers jobs. Graphic Arts: Reference Collection Oversize Z232.P99 A9f

Volume one:Copy of PynsonPrinters_Volume 1

Volume two:Copy of PynsonPrinters_vol.2

Volume three:Copy of PynsonPrinters_vol.3

Volume four:Copy of PynsonPrinters_vol.4 (1) (1)

Extras: Copy of PynsonPrinters_Presses

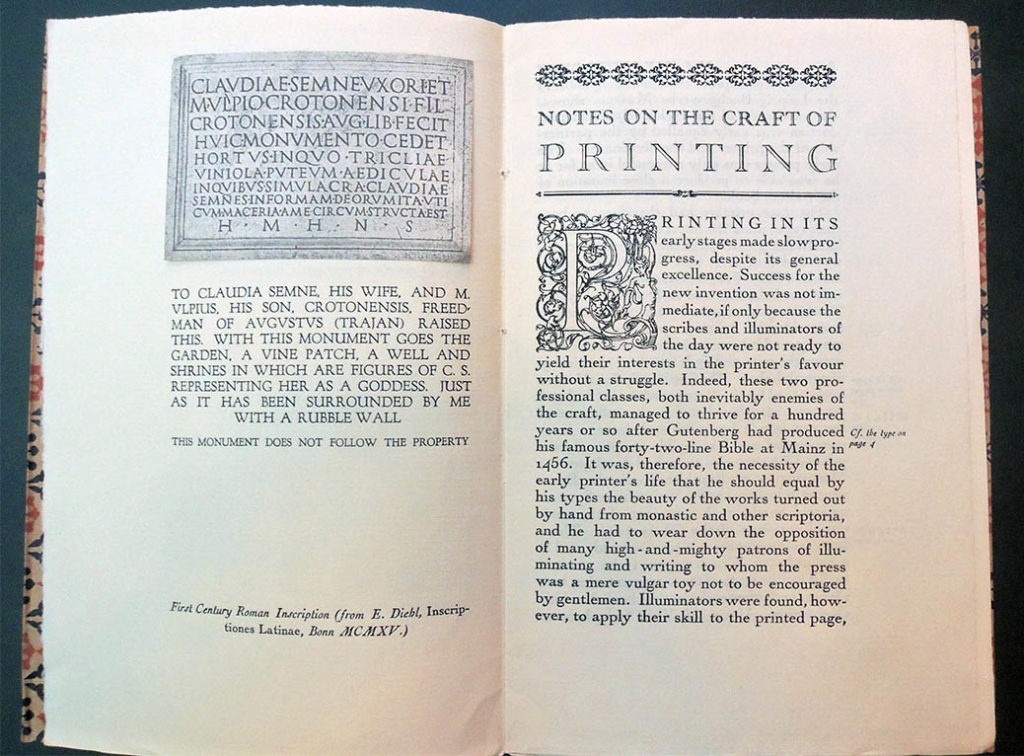

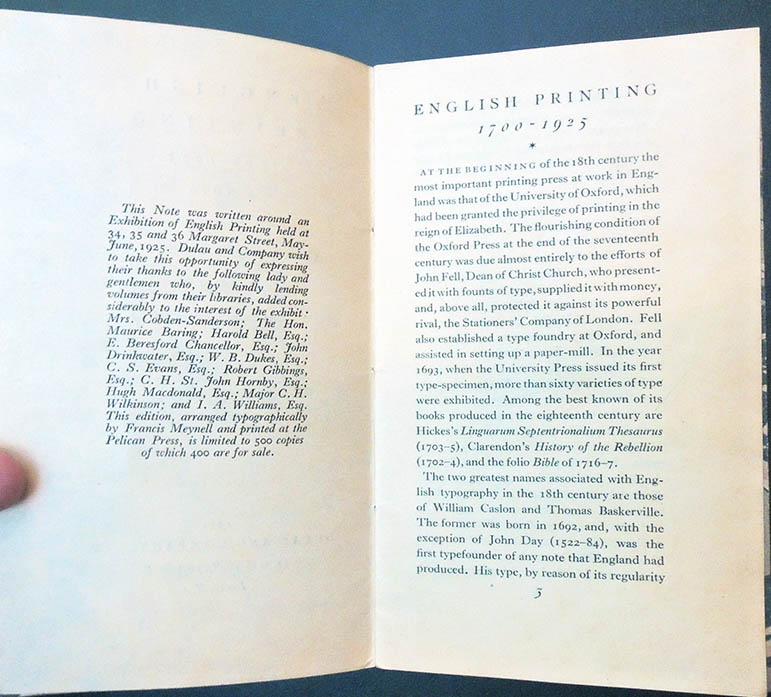

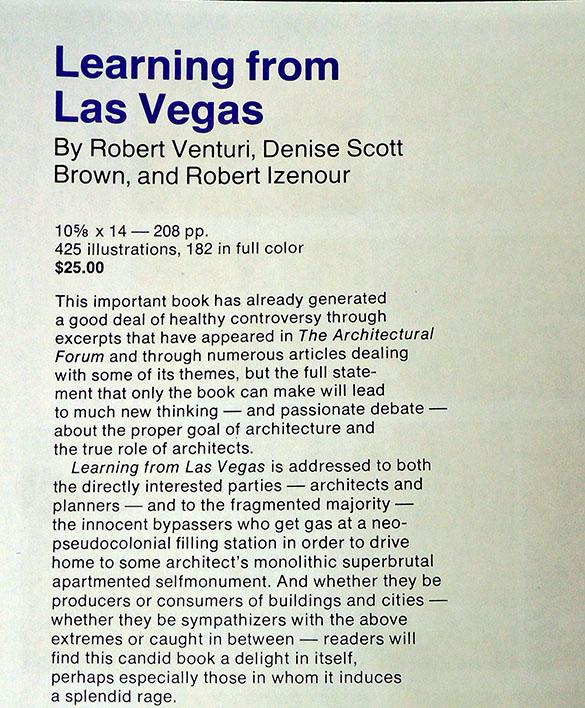

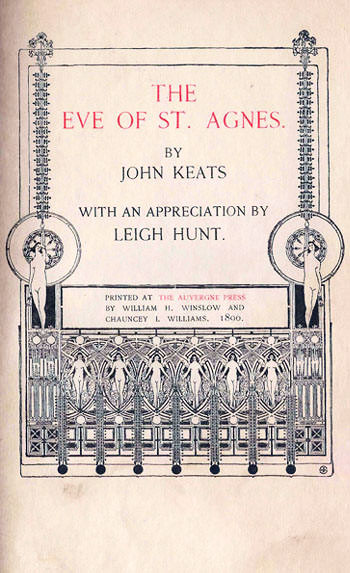

“From the twentieth of March, 1922, the Pynson Printers are at your service for the planning and production of all printing in which quality is the first consideration. We have founded our organization on the belief that the printer should be primarily an artist—a designer and a creator rather than a mere manufacturer. Toward this end, we have assembled a group whose several abilities and varied experience cover every phase of the art and business of printing. . . . We will do no work in which quality must be sacrificed to exigencies of time or cost” (Reprinted in Lawrance Thompson “Forty Mercer Street,” Princeton University Library Chronicle 2, no. 1 (November 1940): 32).

“From the twentieth of March, 1922, the Pynson Printers are at your service for the planning and production of all printing in which quality is the first consideration. We have founded our organization on the belief that the printer should be primarily an artist—a designer and a creator rather than a mere manufacturer. Toward this end, we have assembled a group whose several abilities and varied experience cover every phase of the art and business of printing. . . . We will do no work in which quality must be sacrificed to exigencies of time or cost” (Reprinted in Lawrance Thompson “Forty Mercer Street,” Princeton University Library Chronicle 2, no. 1 (November 1940): 32).

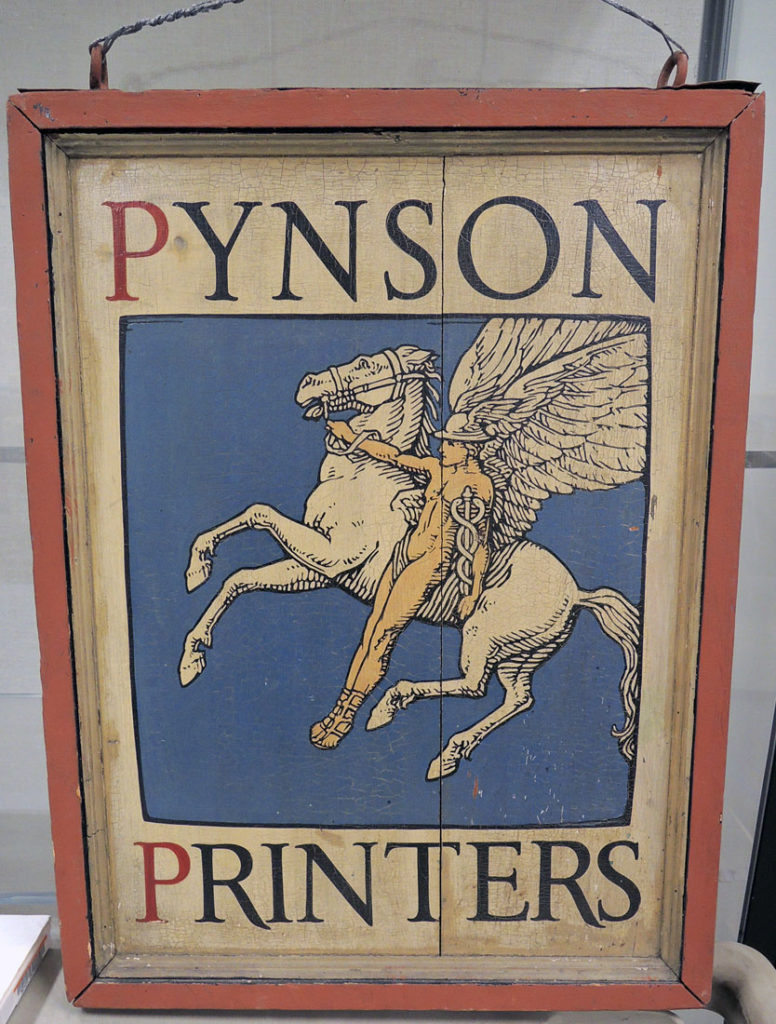

Together with designers Walter Dorwin Teague (1883-1960), Hubert L. Canfield, and David Silvé, Adler opened a small, fine press printing shop at 122 East 32nd Street named Pynson Printers, after the sixteenth-century printer Richard Pynson.

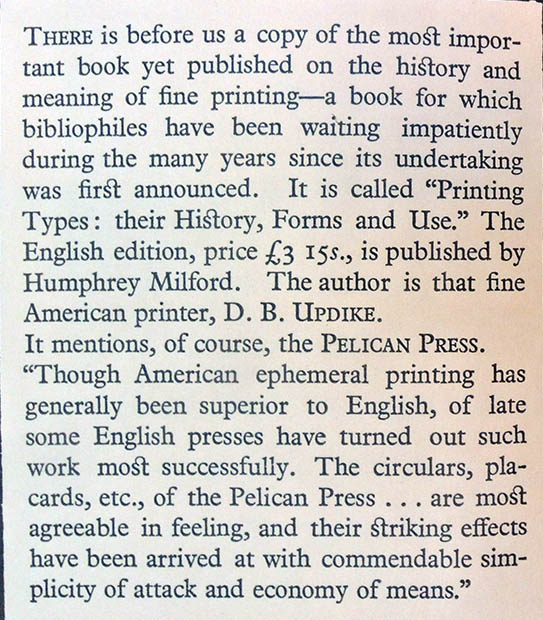

Within six months, the others had moved on, leaving Adler the sole owner of the firm (see: John F. Peckham “Forty Mercer,” Princeton Alumni Weekly 41, no. 12 (December 16, 1940): 8). As stated in the opening announcement, concerns with quality rather than commercial practicality led production. To that end, he sought out artisans, publishers, and clients who shared his love of typography and fine printing.

Within six months, the others had moved on, leaving Adler the sole owner of the firm (see: John F. Peckham “Forty Mercer,” Princeton Alumni Weekly 41, no. 12 (December 16, 1940): 8). As stated in the opening announcement, concerns with quality rather than commercial practicality led production. To that end, he sought out artisans, publishers, and clients who shared his love of typography and fine printing.

The Pynson Printers office moved to the New York Times building at 239 West 43rd Street, elegantly decorated by Lucien Bernhard. In a 1925 letter to Rockwell Kent (1882-1971), with whom he was already in business, Adler wrote, “Since you were last here Mr. [Lucien] Bernhard has arranged to build a studio adjoining our shop which will help create more of the kind of thing we want to have….” (Adler to Kent, February 13, 1925. CO262, box 32, Adler papers). These three men, Adler, Kent, and the recently emigrated German designer Lucien Bernhard (1883-1972), began working together on a variety of printing and design projects.

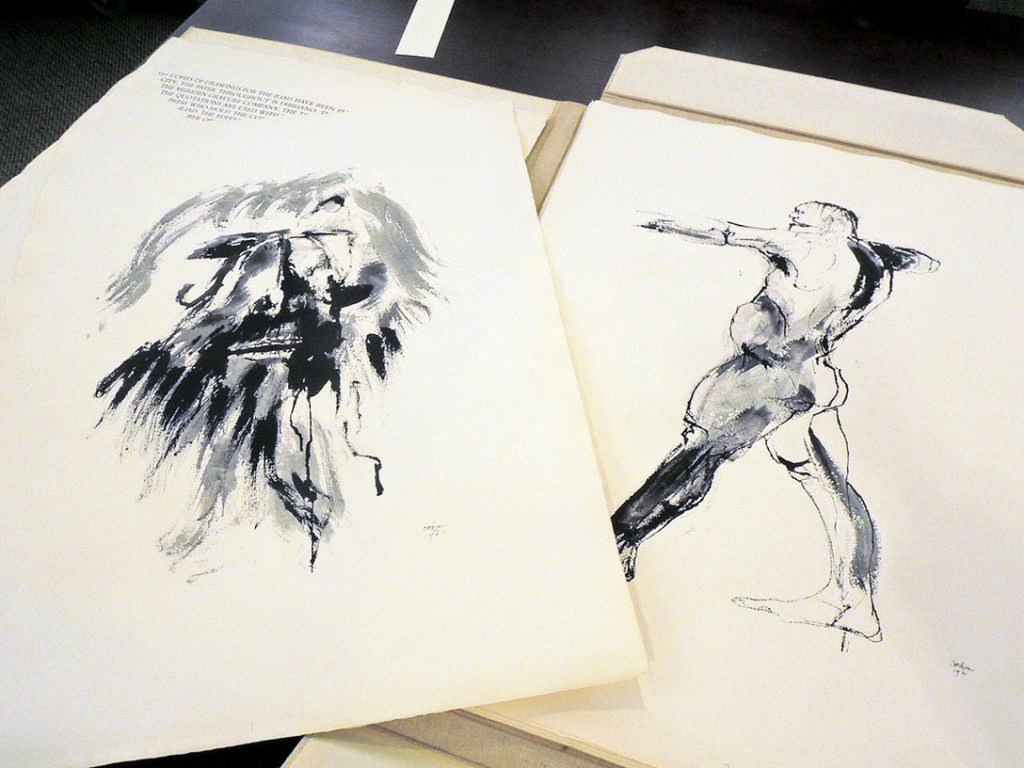

Their first fine press book, Candide, began in 1925 when 27-year-old Bennett Cerf and his 23-year-old friend Donald Klopfer decided they wanted a business of their own. Cerf was vice-president at the publishing house of Boni & Liveright and interested in the firm’s catalog of 109 titles published under the Modern Library imprint. Klopfer and Cerf raised $215,000 to purchase the imprint and then, set about to redefine the Modern Library to make it distinctly their own.

“We went to a man I had heard was a great typographer named Elmer Adler, who headed the Pynson Printers,” said Cerf. “He was so good that he was allowed to have his office in the New York Times building . . . Elmer Adler was an elegant gentleman whose family headed the Adler Rochester clothing company. It was beautiful, beautiful work that he turned out at only about eight times what it should have cost . . . Elmer helped us redesign modern library [and] helped us find the man to design the flying girl with the torch. . . So the modern library had a new dress that was very stylish,” (Bennett Cerf oral history, p. 144. Columbia University Libraries).

“We were talking about doing a few books on the side,” recalled Cerf, “when suddenly I got an inspiration and said, ‘We just said we were going to publish a few books on the side at random. Let’s call it Random House.’” Kent was so taken with the idea he offered to draw them a trademark on the spot and five minutes later handed Cerf the Random House symbol, which has been on their colophon ever since.

“We were talking about doing a few books on the side,” recalled Cerf, “when suddenly I got an inspiration and said, ‘We just said we were going to publish a few books on the side at random. Let’s call it Random House.’” Kent was so taken with the idea he offered to draw them a trademark on the spot and five minutes later handed Cerf the Random House symbol, which has been on their colophon ever since.

Candide was a success but Adler’s partnership with Random House was short-lived. “Elmer didn’t cotton to trade publishing . . . He was a very difficult partner anyway—very querulous and dictatorial, and he wanted to do everything his way, and when we wanted to have other printers do books, Elmer was very jealous.”

Candide was a success but Adler’s partnership with Random House was short-lived. “Elmer didn’t cotton to trade publishing . . . He was a very difficult partner anyway—very querulous and dictatorial, and he wanted to do everything his way, and when we wanted to have other printers do books, Elmer was very jealous.”

Cerf and Klopfer bought out his share, even though he never put up any money to join them. Adler continued to do business with Random House and Cerf remained a stockholder in the Pynson Printers. Kent did business with them both and joined Bernhard in founding a design firm they named Contempora.

Adler closed the Pynson Printers in 1940, when he was invited to move to Princeton, New Jersey, and established a department of Graphic Arts for Princeton University. He brought with him a personal collection—fourteen tons of books, prints, paintings, records, and equipment—which became the basis for the graphic arts collection we enjoy today. Although he donated some records of the Pynson Press to the NYPL in 1936, he retained a large amount of material with which to teach, including papers, proofs, and plates, which he sold to the Princeton University Library in 1948 for one dollar.