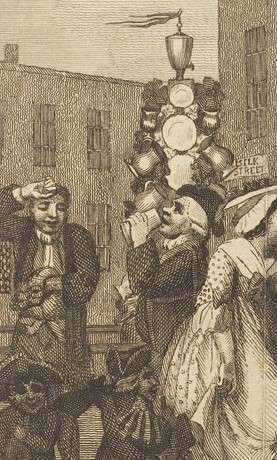

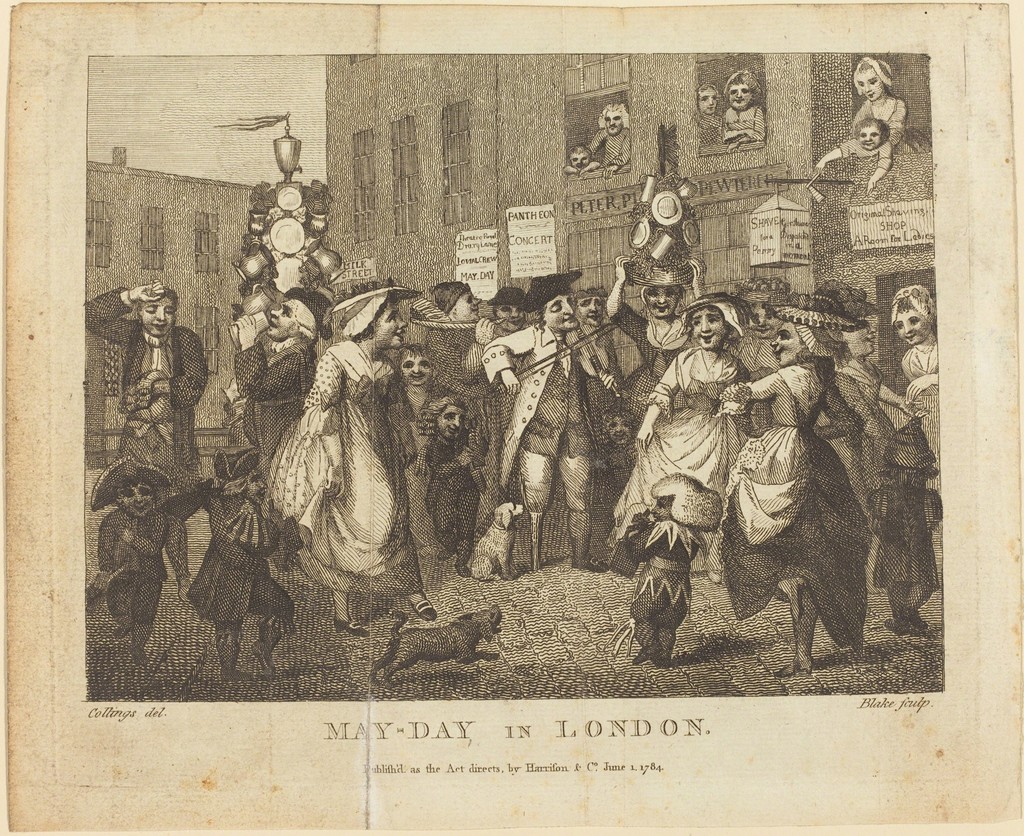

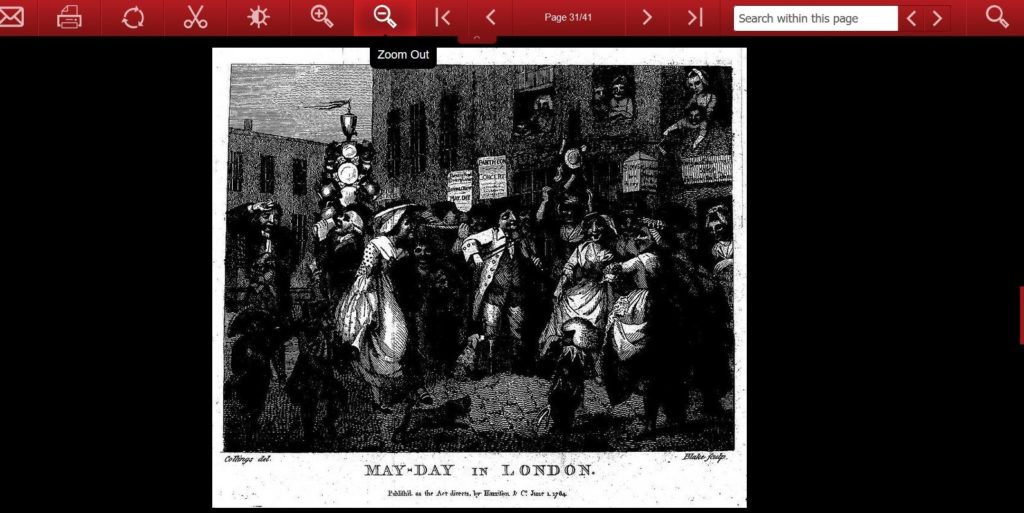

William Blake (1757-1827) after Samuel Collings (active 1784-1795), May-Day in London. Folding frontispiece to the v.1, May 1, 1784 issue of Wit’s Magazine (London, 1784). Etching. Also published as an individual print dated June 1, 1784 by Harrison and Company, London.

William Blake (1757-1827) after Samuel Collings (active 1784-1795), May-Day in London. Folding frontispiece to the v.1, May 1, 1784 issue of Wit’s Magazine (London, 1784). Etching. Also published as an individual print dated June 1, 1784 by Harrison and Company, London.

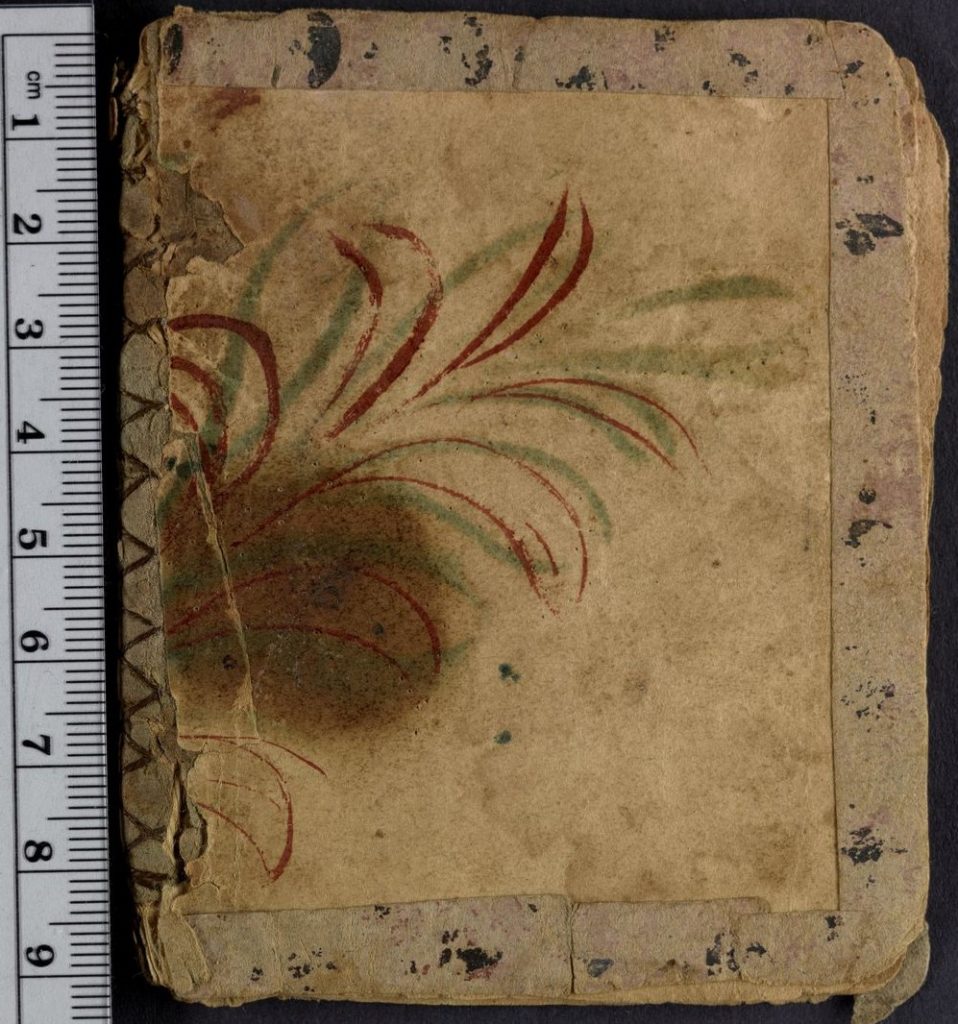

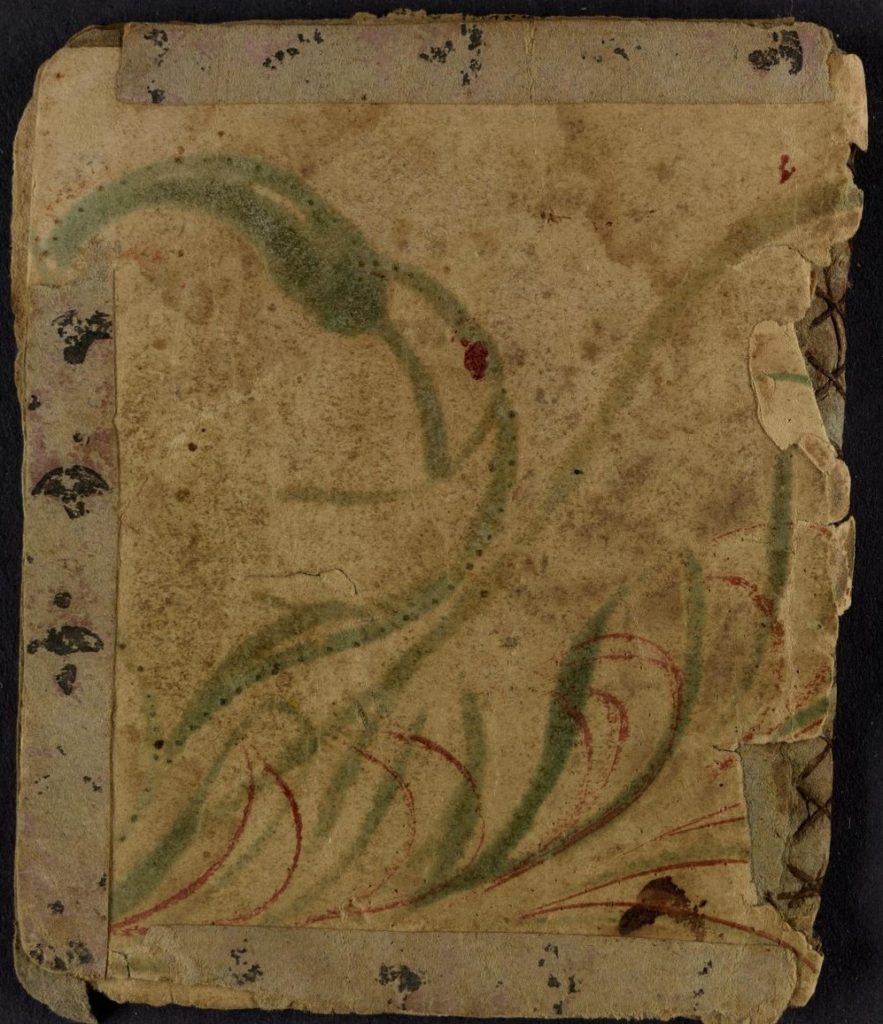

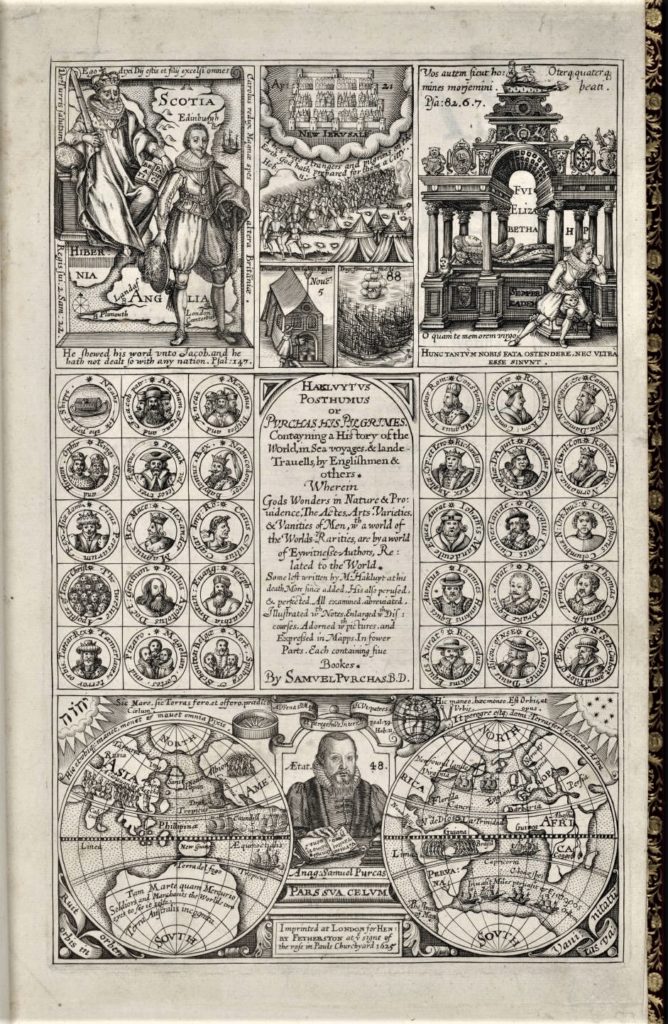

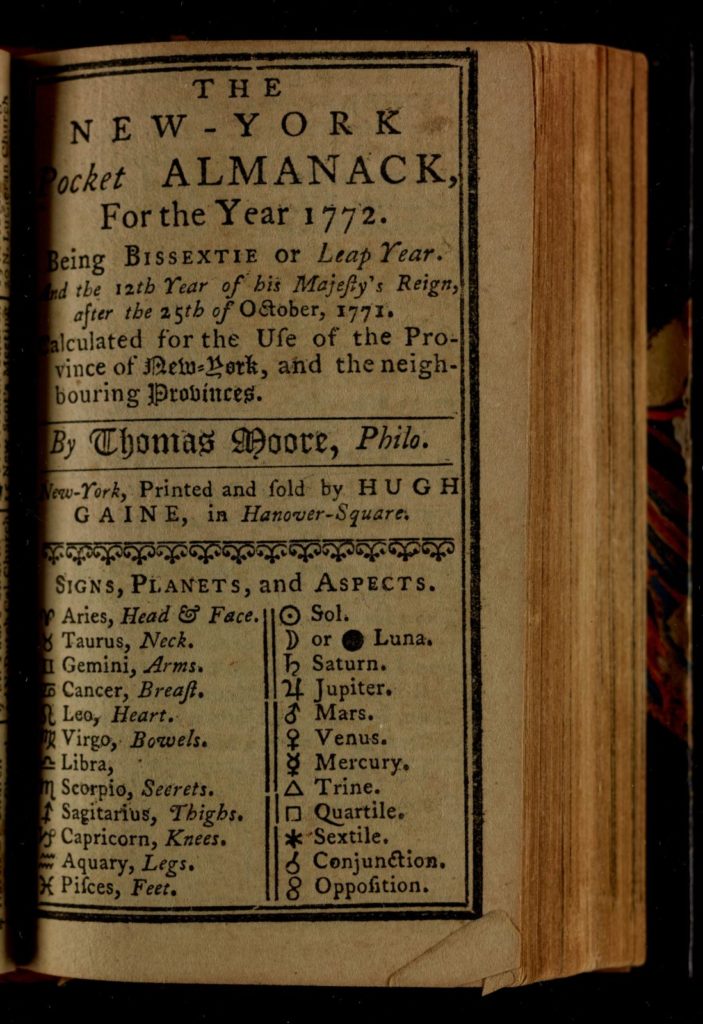

One of the best-loved prints to celebrate this festive day is William Blake’s etching “May-Day in London” commissioned for the frontispiece in the May 1, 1784 issue of The Wit’s Magazine; or, Library of Momus. Being a compleat repository of mirth, humour, and entertainment… , edited by Thomas Holcroft (London, Printed for Harrison and Co., 1784-84). Rare Books 0901.981 v.1-2.

There are numerous folding plates throughout the magazine’s run, five etched by Blake; one after a design by Thomas Stothard and four after designs by Samuel Collings. The print is announced on the title page: “with a large quarto engraving representing a curious description of May-Day in London, as mentioned in Sammy Sarcasm’s Epistle to his Aunt; designed by Mr S. Collings and engraved by Mr. W. Blake purposely for this work.

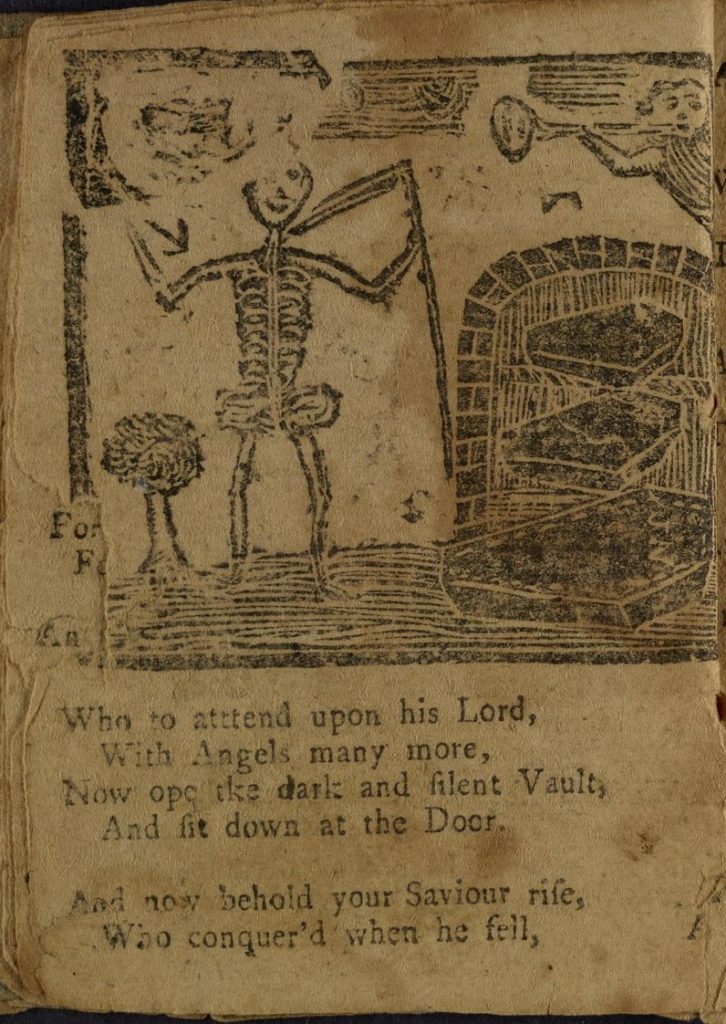

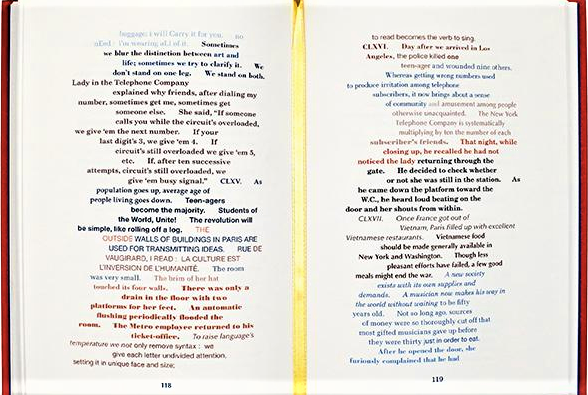

While Princeton University Library has a beautiful set of Wit’s Magazine with all the original Blakes bound in, there is no access to the paper issue this week. Several digital surrogates are offered by our online catalogue but they present the reader with this unfortunate image [below], not much good for study or entertainment. The digital image at the top is from the National Gallery of Art.

https://access-newspaperarchive-com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/uk/middlesex/london/wits-magazine/

https://access-newspaperarchive-com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/uk/middlesex/london/wits-magazine/

Blake’s prints appear in successive issues from February to May 1784 and show an uncharacteristic side of the artist’s talent. In the study “Puzzling the Reader,” Gregg Hecimovich points out that,

“The Wit’s Magazine represents the first known contact between [Thomas] Holcroft and Blake, and it was from about this time that Blake began to move in the circle of radicals, including Godwin, Wollstonecraft, and Horne Tooke, in which Holcroft figured so prominently. Although Blake had been employed to engrave illustrations for publications such as the Novelist’s Magazine, it seems clear that his connection with the Wit’s Magazine was through Holcroft. Blake’s friend Thomas Stothard designed the illustration for the first issue but, despite the replacement of Stothard with Samuel Collings, Blake stayed on as engraver until just after Holcroft resigned as editor in May 1784. For Blake, who had recently married and established a household independent of his father, such commissions provided much-needed income, but he probably also felt the attraction of working with the dynamic and provocative Holcroft.” –Gregg A. Hecimovich, Puzzling the Reader: Riddles in Nineteenth-century British Literature (2008): 32.

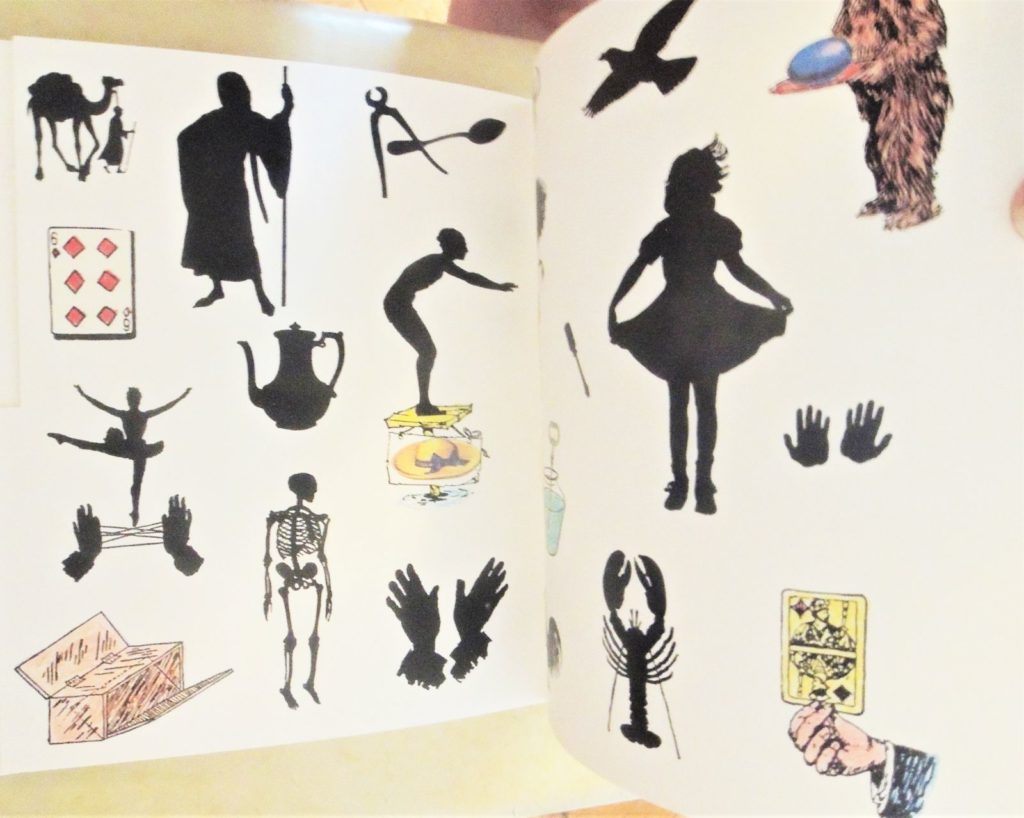

This frontispiece (often rebound next to the poem in section two) presents a busy London street on May-Day with milkmaids, chimney sweepers, a violinist, and others. Notice that the violinist has a wooden leg. Unlike many pastoral scenes, Collings’ design and Blake’s rendering feature an underprivileged population of London rather than the beautiful people.

Hecimovich calls this the most powerful of all Blake’s contributions to Wit’s Magazine. He writes, “…the traditional May-Day festivities are inverted into a sordid anti-pastoral. Beneath a maypole hung not with flowers but with dirty pots and pans, a crippled one-eyed fiddler plays for drunken clergymen, lascivious milkmaids, child-age chimney sweeps, and assorted other street people.”

He goes on to question whether or not there was a direct influence on later Blake poems such as The Chimney Sweep and London, commenting that this is “perhaps the earliest instance of Blake’s exploring and depicting through the new verbal and pictorial mediums the degeneracy of urban London life.”

Blake aside, Samuel Collings was a interesting amateur draughtsman, caricaturist, and genre painter who remains understudied by art historians. He mainly worked in London, exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1784-89. He received commissions from The Bon-Ton Magazine in the 1790s as well as The Wit’s Magazine and others. Collings may have used the pseudonym Annibal Scratch and others, leaving good work without attribution. Princeton holds a unique portfolio of Thomas Rowlandson etchings after drawings by Collings, commissioned by the Marylebone publisher E. Jackson to illustrate Boswell’s Tour to the Hebrides. See more: https://www.princeton.edu/~graphicarts/2012/09/the_journey_of_dr_johnson_and.html