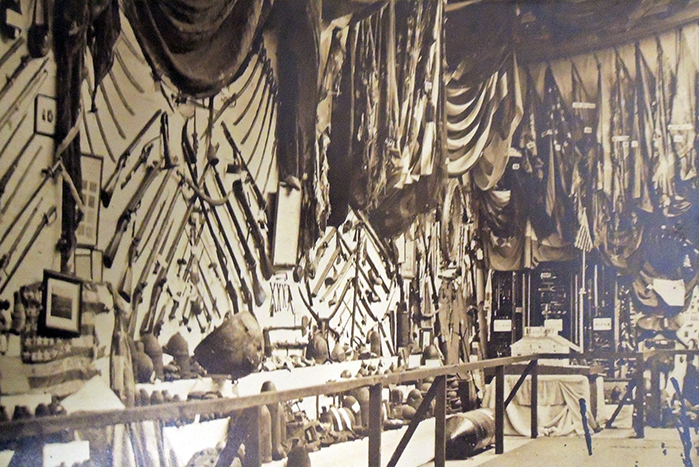

“View in the Wigwam” by J. Gurney and Son, Photographers

“View in the Wigwam” by J. Gurney and Son, Photographers

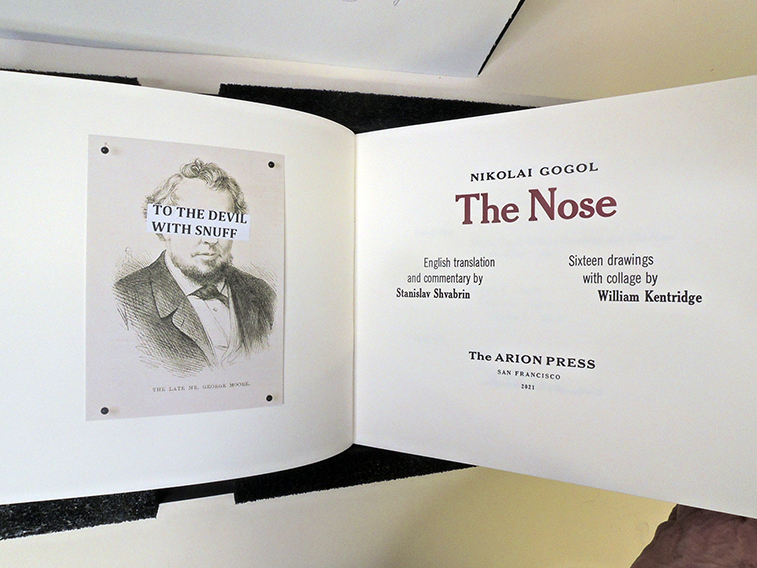

A Record of the Metropolitan Fair: in aid of the United States Sanitary Commission, held at New York, in April, 1864, with photographs. New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1867. John Shaw Pierson Civil War Collection, W25.67.6

A Record of the Metropolitan Fair: in aid of the United States Sanitary Commission, held at New York, in April, 1864, with photographs. New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1867. John Shaw Pierson Civil War Collection, W25.67.6

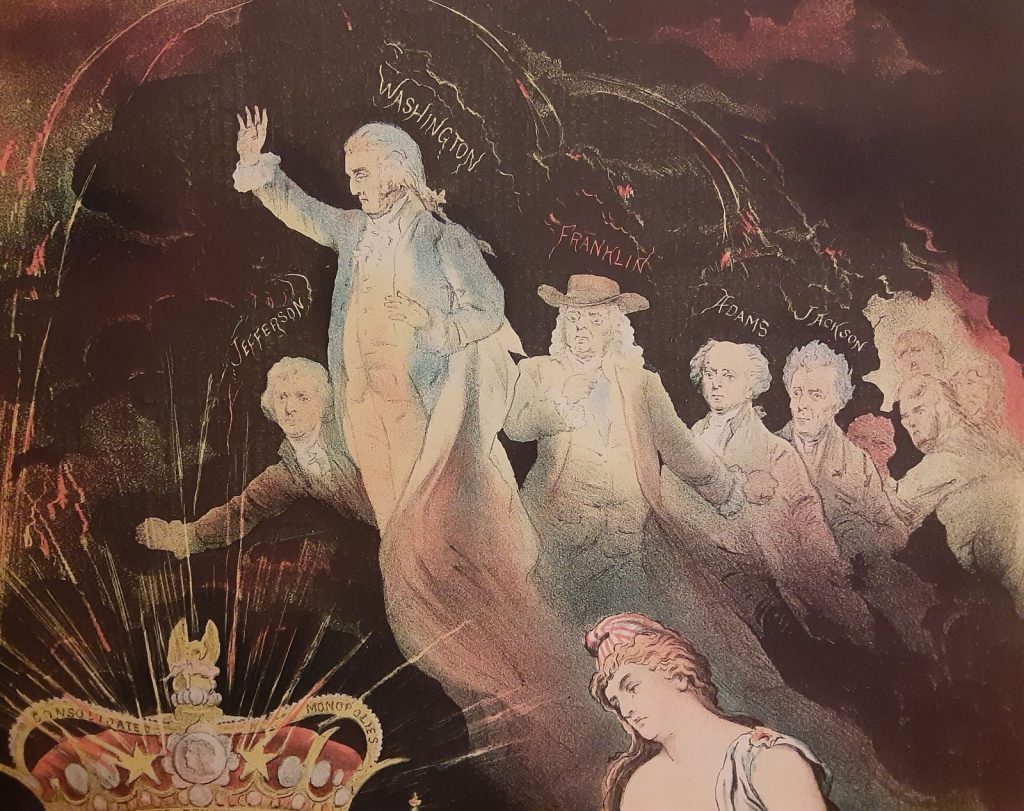

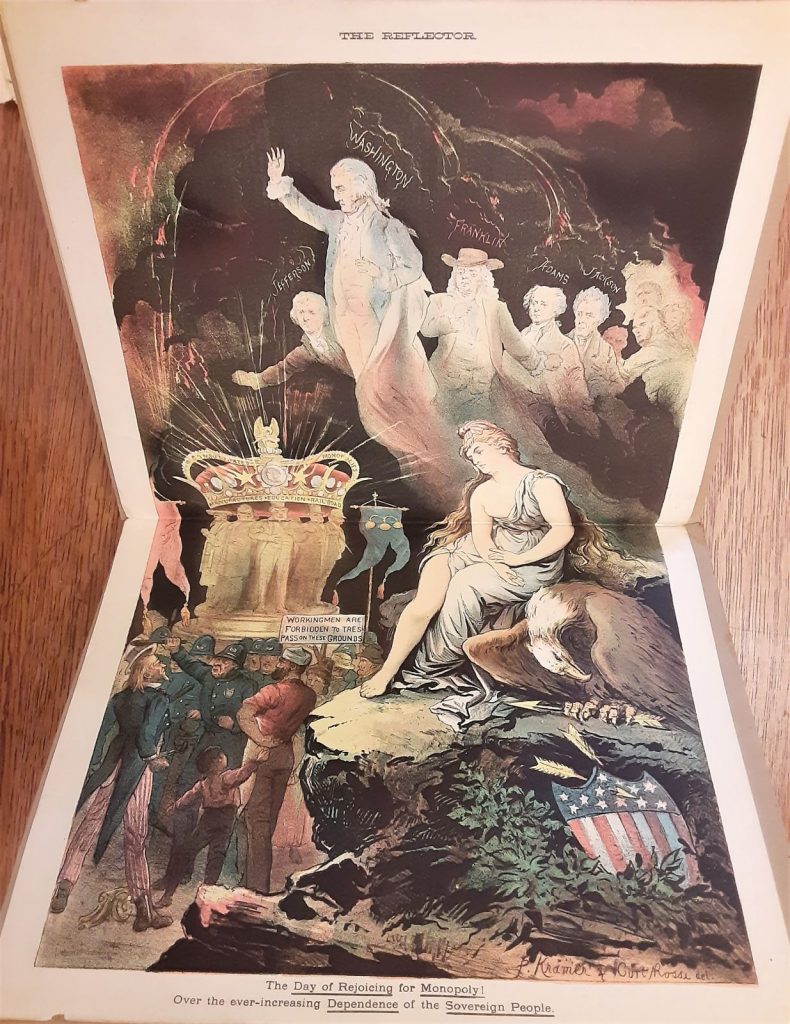

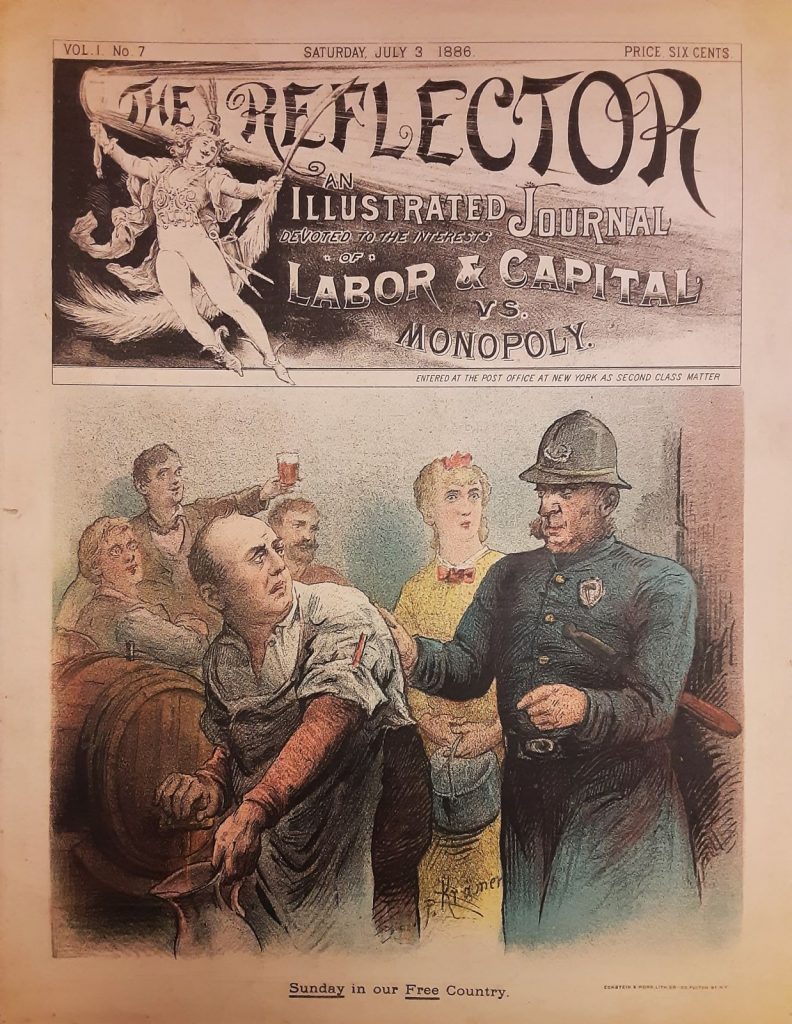

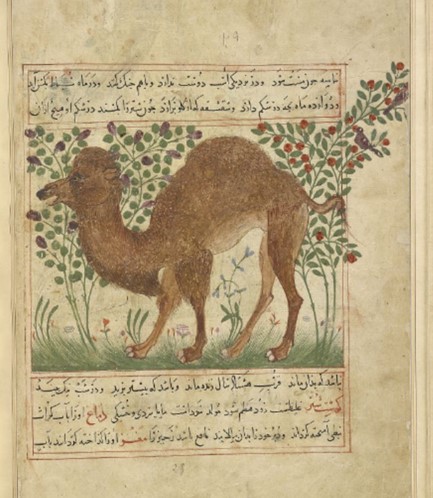

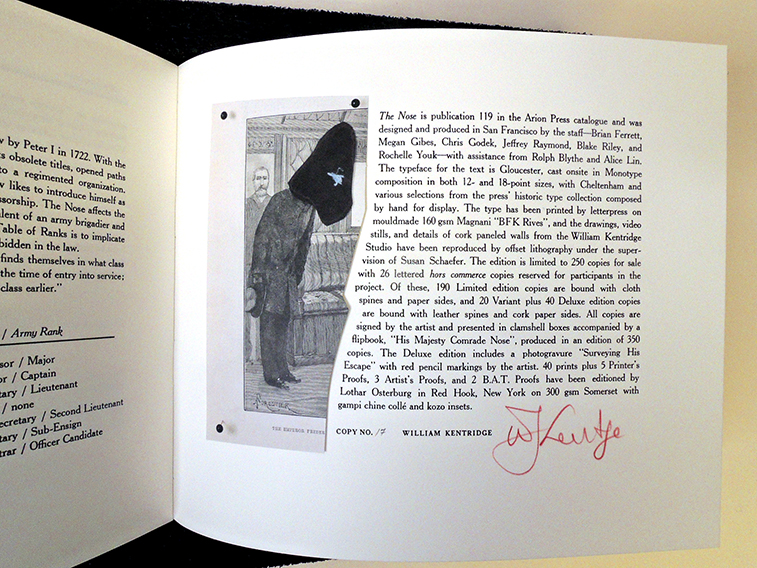

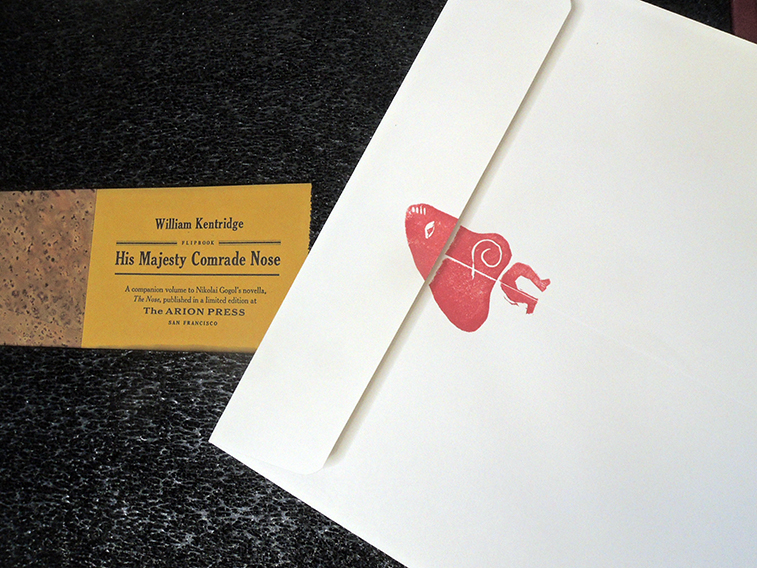

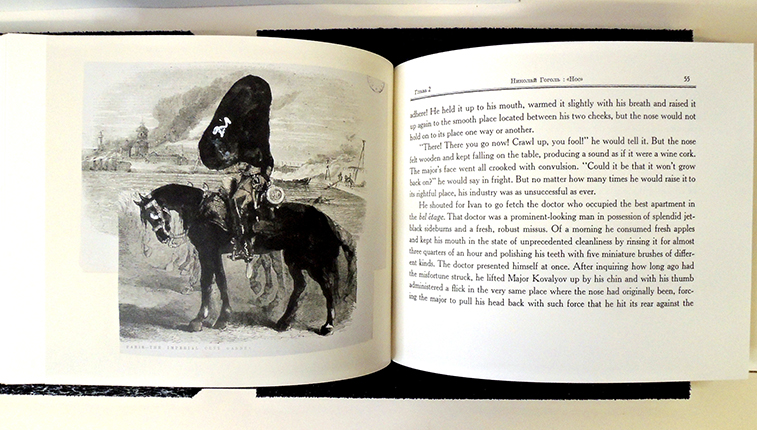

Following on the success of the Chicago Sanitary Fair in 1863, the Metropolitan City of New York’s Sanitary Commission organized their own fair to raise money for Union Army soldiers and their families. Privately funded and managed primarily by female volunteers, the fair would help with the soldiers’ back pay, distribute supplies to camp hospitals, and support other organizations hurt by the American Civil War.

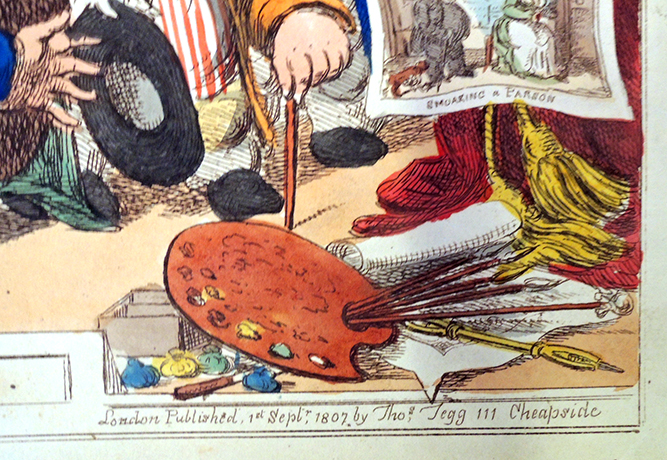

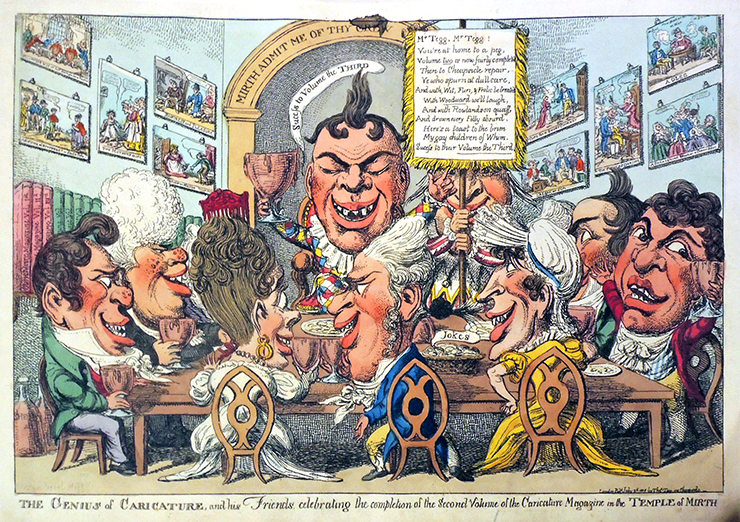

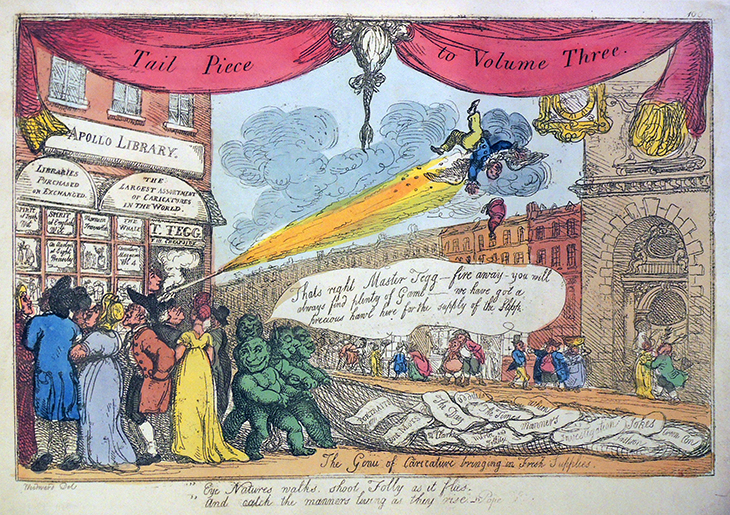

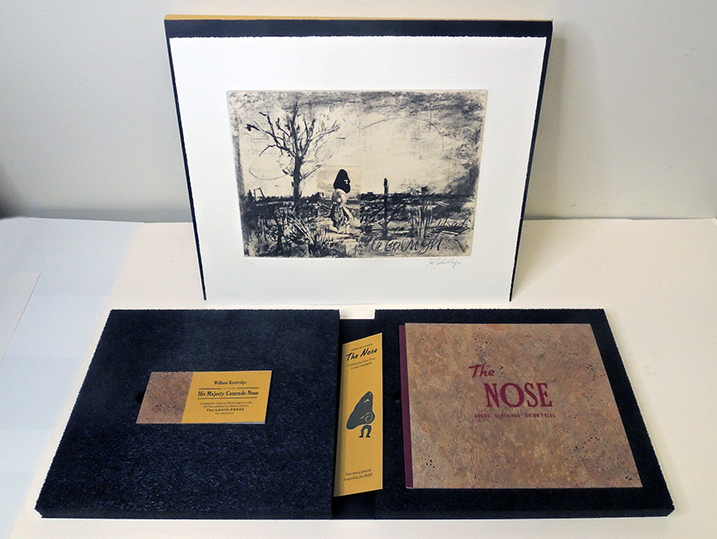

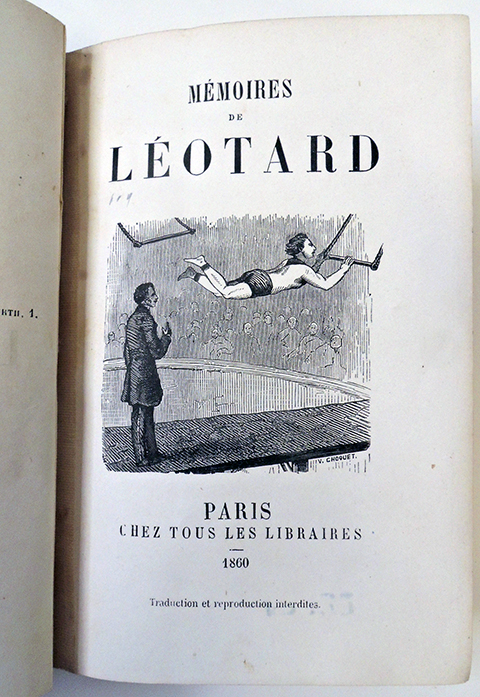

After several delays, the Metropolitan Fair was held from April 4 to 23, 1864, and raised $1,34 million dollars. Several years later, A Record of the Metropolitan Fair was published, printed at the distinguish Riverside Press of H.O. Houghton, with 8 original albumen photographs pasted in every volume, after negatives by the celebrated photographer Jeremiah Gurney (1812-1895) and the practically unknown Maurice Stadtfeld (ca.1831-1881). Princeton owns a copy collected at the time of publication by John Shaw Pierson, class of 1840, whose thousands of gifts to the library began arriving in 1869.

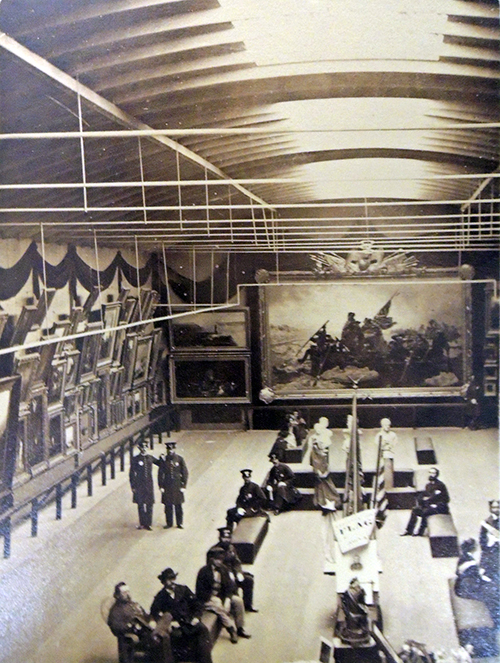

“View in the Art Gallery” by J. Gurney and Son, photographers.

“View in the Art Gallery” by J. Gurney and Son, photographers.

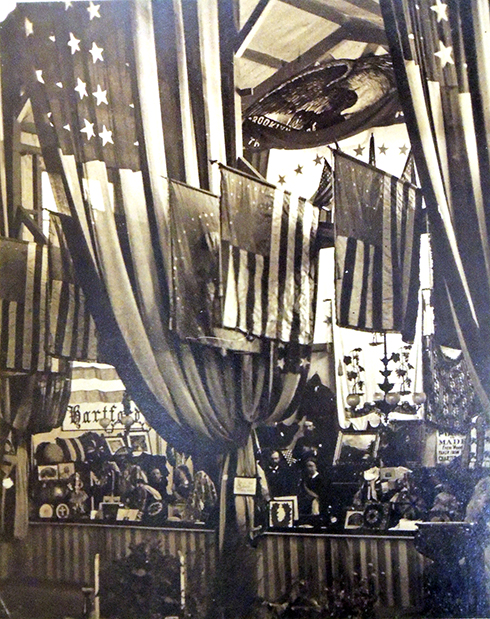

“Hartford Booth” by M. Stadtfeld, photographer.

“Hartford Booth” by M. Stadtfeld, photographer.

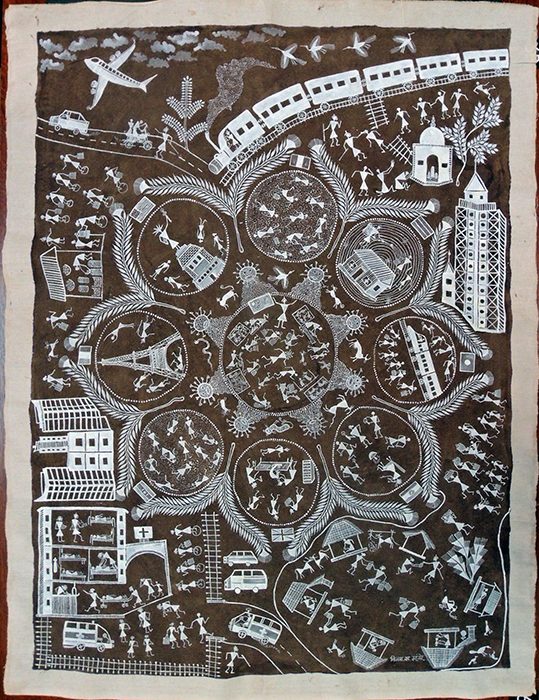

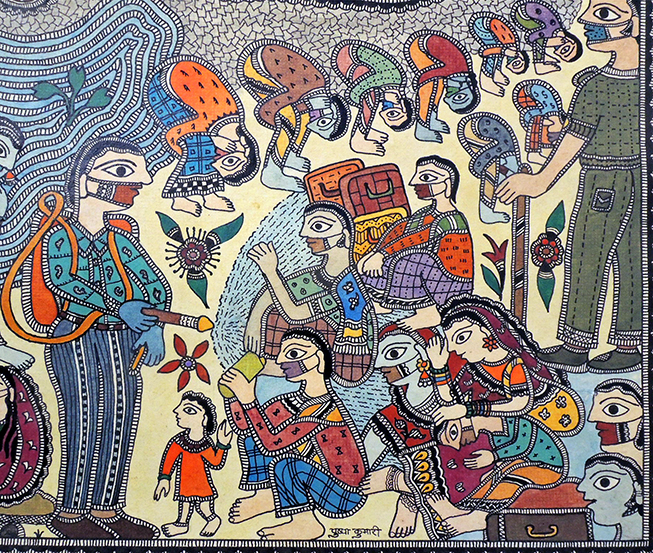

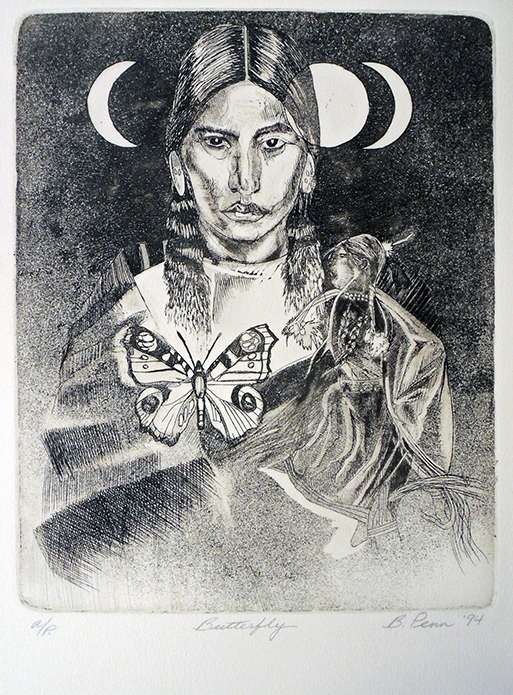

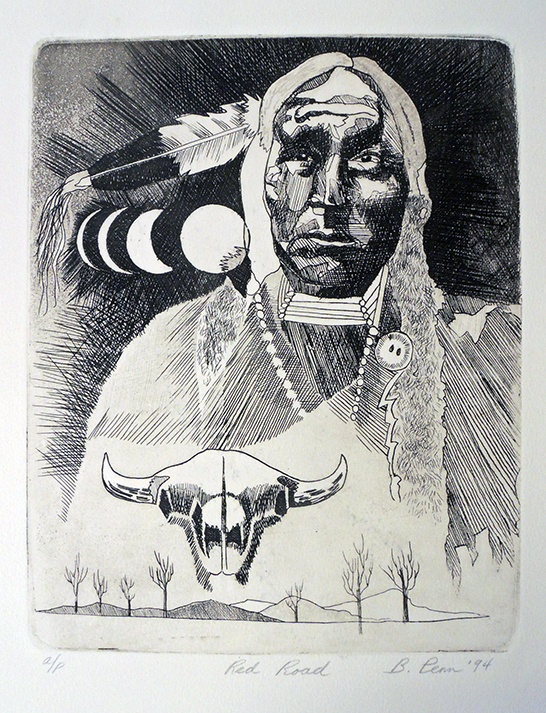

A season ticket to the Metropolitan Fair was $5, which allowed visitors to attend all the events and see all the displays at the 22nd Regiment Armory, 125 West 14th Street, as well as the other buildings and venues constructed solely for the three weeks of the fair. Performances were held by an international array of musicians including indigenous Americans who brought their own buffalo-skin teepee in which to perform. Cooking demonstrations took place in the Knickerbocker Kitchen, rare books and manuscripts were sold at the Metropolitan Book Department on the second floor while a working photography studio operated on the third floor. Barrels of free clothing and other items were offered to anyone who might be in need.

A season ticket to the Metropolitan Fair was $5, which allowed visitors to attend all the events and see all the displays at the 22nd Regiment Armory, 125 West 14th Street, as well as the other buildings and venues constructed solely for the three weeks of the fair. Performances were held by an international array of musicians including indigenous Americans who brought their own buffalo-skin teepee in which to perform. Cooking demonstrations took place in the Knickerbocker Kitchen, rare books and manuscripts were sold at the Metropolitan Book Department on the second floor while a working photography studio operated on the third floor. Barrels of free clothing and other items were offered to anyone who might be in need.

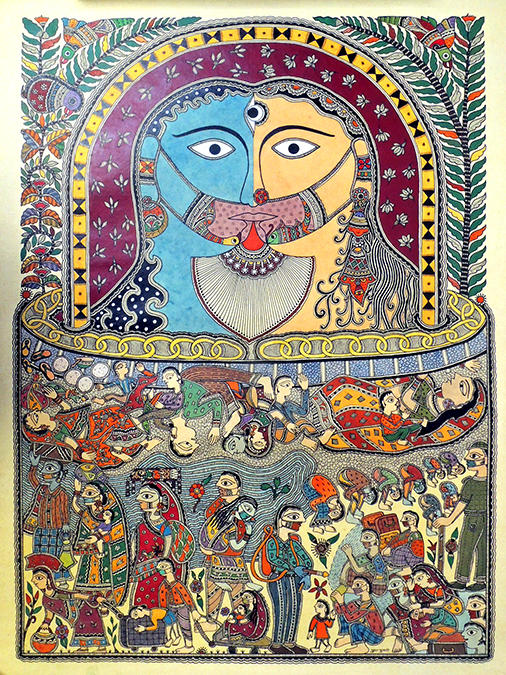

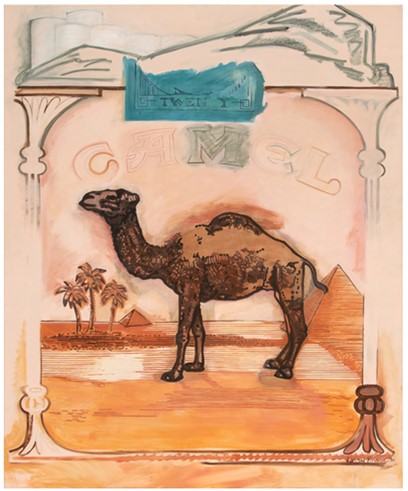

In the main hall of the Armory, an exhibition of paintings was hung including Albert Bierstadt’s Rocky Mountains opposite Frederic Edwin Church’s Heart of the Andes; and in the center Emanuel Leutze’s mammoth Washington Crossing the Delaware. Leutze’s original painting of this scene had been destroyed and so, in 1850 he painted a second version purchased by Marshall O. Roberts that was lent to the Fair. Later the painting was given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art by John Stewart Kennedy.

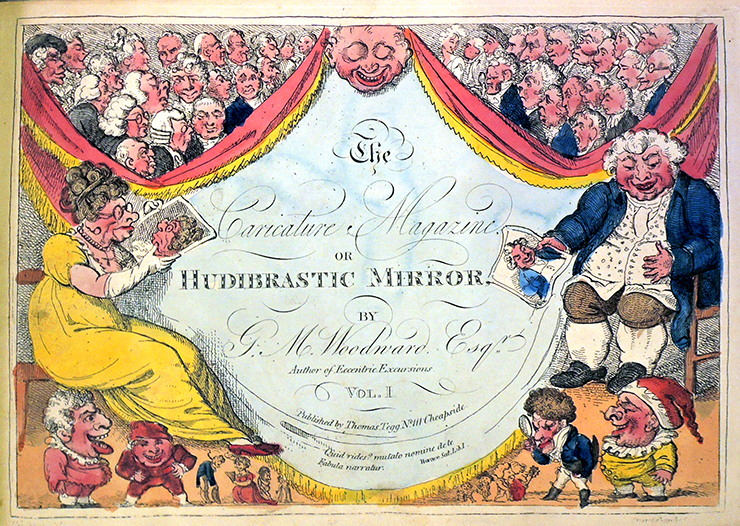

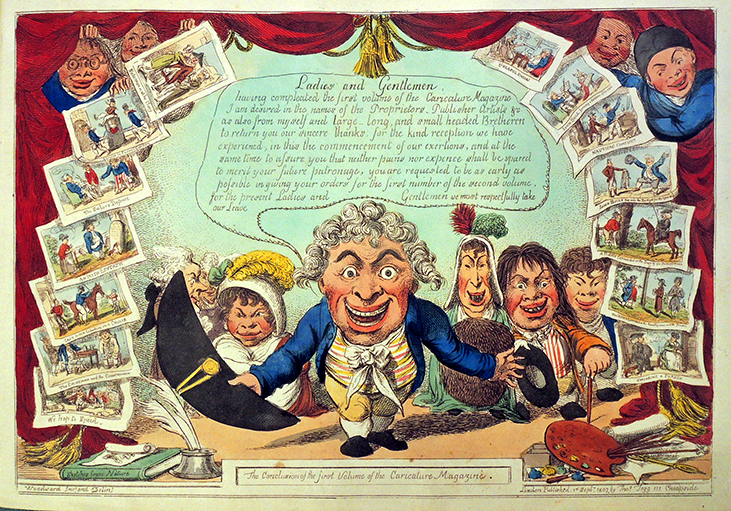

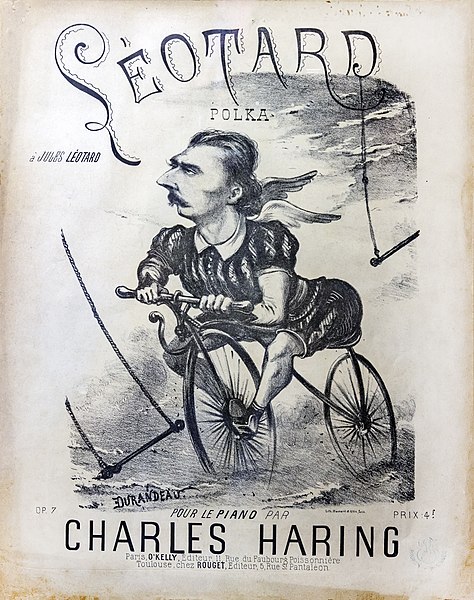

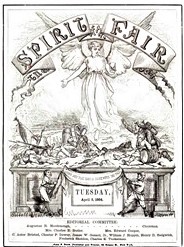

A newspaper called The Spirit of the Fair was published daily with a serial essay by James Fenimore Cooper to make sure people read each issue. The main contract for images from the fair went to Jeremiah Gurney whose elegant gallery was nearby at 707 Broadway. J. Gurney & Sons produced the majority of the official photographs sold or distributed during the fair from the Armory and afterwards at their own studio. Two of the prints included in The Record of the Metropolitan Fair are credited to Maurice Stadtfeld, whose studio was just up the block from Gurney at 711 Broadway. Only recently established in New York, Stadtfeld may have been engaged by Gurney and his son Benjamin to help with the enormous demand for prints.

A newspaper called The Spirit of the Fair was published daily with a serial essay by James Fenimore Cooper to make sure people read each issue. The main contract for images from the fair went to Jeremiah Gurney whose elegant gallery was nearby at 707 Broadway. J. Gurney & Sons produced the majority of the official photographs sold or distributed during the fair from the Armory and afterwards at their own studio. Two of the prints included in The Record of the Metropolitan Fair are credited to Maurice Stadtfeld, whose studio was just up the block from Gurney at 711 Broadway. Only recently established in New York, Stadtfeld may have been engaged by Gurney and his son Benjamin to help with the enormous demand for prints.

“View in Arms and Trophies Room” by J. Gurney and Son, photographers

“View in Arms and Trophies Room” by J. Gurney and Son, photographers

“View in Curiosity Shop” by J. Gurney and Son, photographers

“View in Curiosity Shop” by J. Gurney and Son, photographers

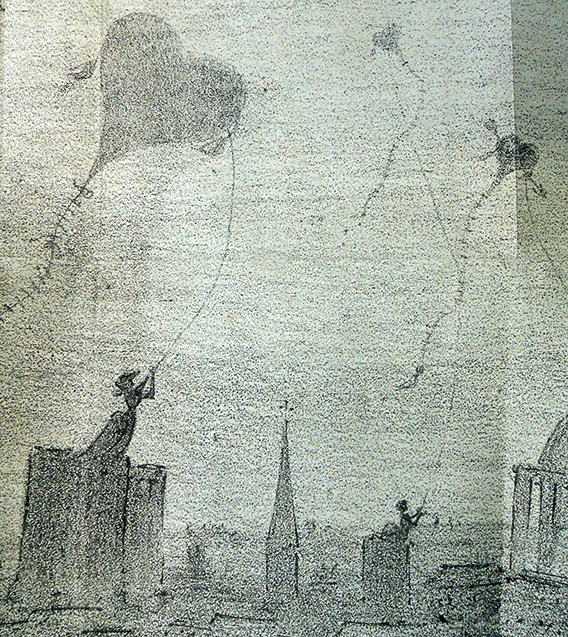

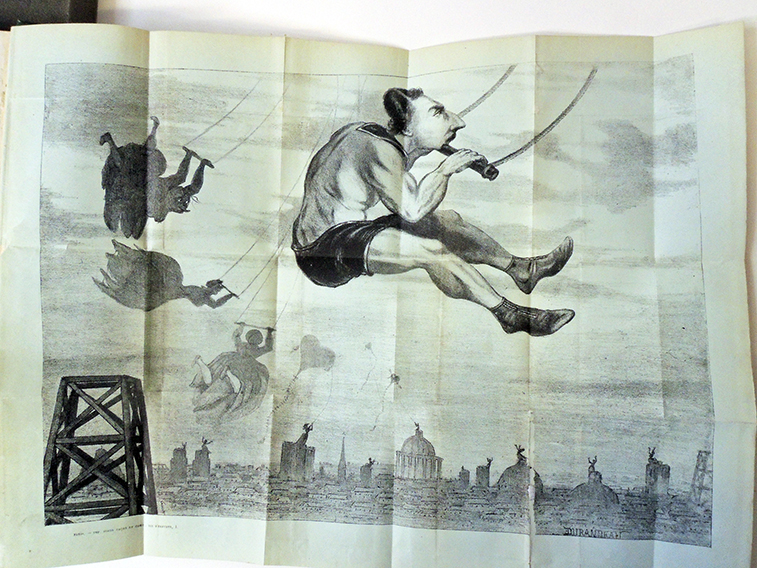

“Irving Cockloft” by J. Gurney and Son photographers

“Irving Cockloft” by J. Gurney and Son photographers

“View in Main Hall, 14th Street Building” by J. Gurney and Son, photographers

“View in Main Hall, 14th Street Building” by J. Gurney and Son, photographers

“Costumes of Ladies in Knickerbocker Kitchen” by M. Stadtfeld, photographer

“Costumes of Ladies in Knickerbocker Kitchen” by M. Stadtfeld, photographer