Davin Kuntze kindly offered our small group a tour of Woodside Press, where Steven Spielberg filmed several scenes for his movie The Post last year. Founded in Woodside, Queens, in 1993, the Press was relocated to the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1998 where it continues to operate today.

Davin Kuntze kindly offered our small group a tour of Woodside Press, where Steven Spielberg filmed several scenes for his movie The Post last year. Founded in Woodside, Queens, in 1993, the Press was relocated to the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1998 where it continues to operate today.

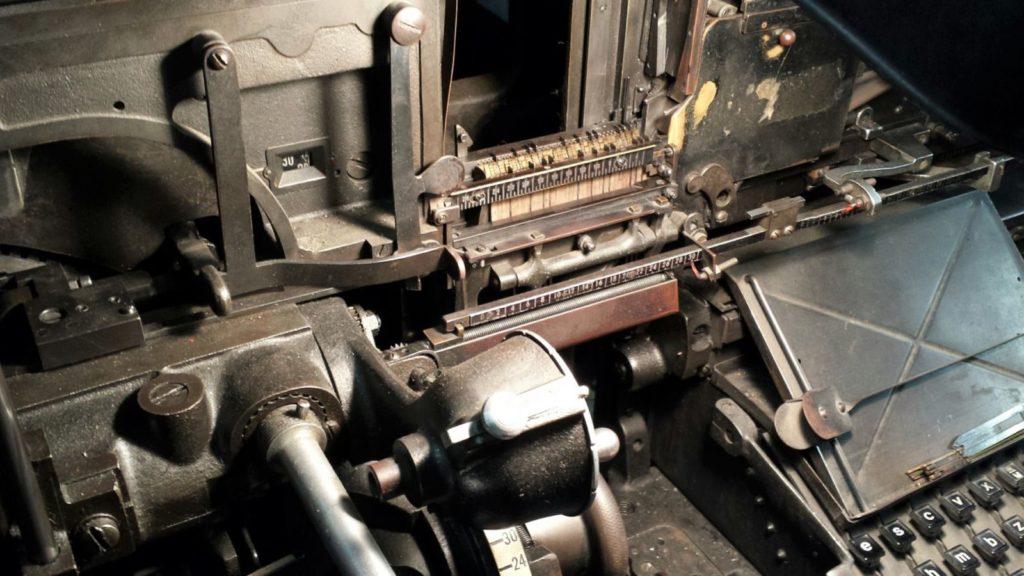

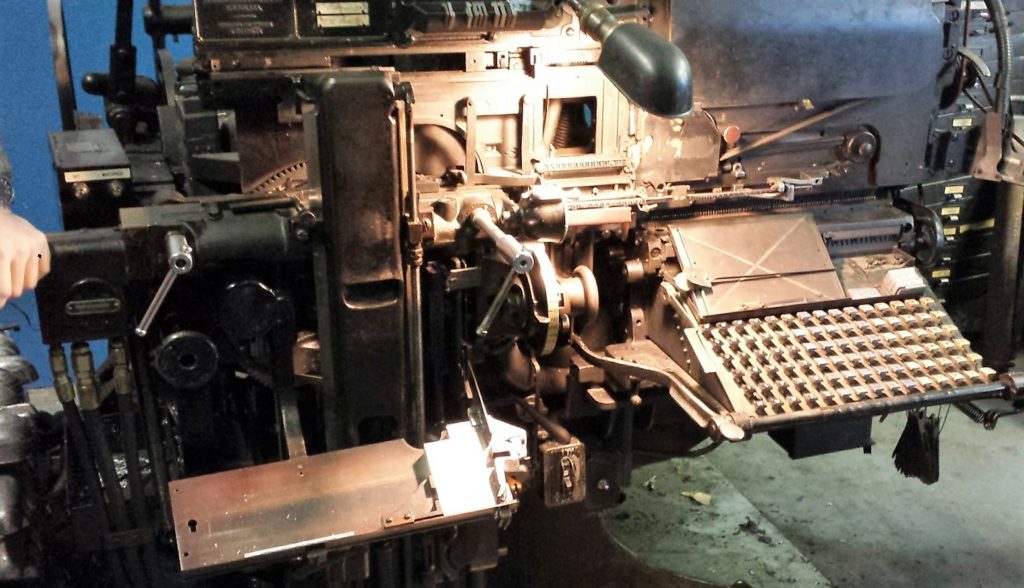

Not only do they offer letterpress printing and binding, the shop has two fully operational Linotype machines with over 200 magazines loaded with Linotype matrices including faces designed by Hermann Zapf, Frederick Goudy, and Rudolph Ruzicka, among others.

These are the machines featured at the end of movie, when Katharine Graham gives the order to print the Pentagon Papers in The Washington Post and the cameras follow the production of the newspaper from editing to distribution. They shot the composing rooms scenes at Woodside Press, just down the street from Steiner Studios.

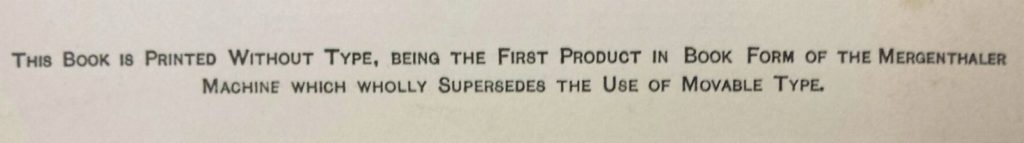

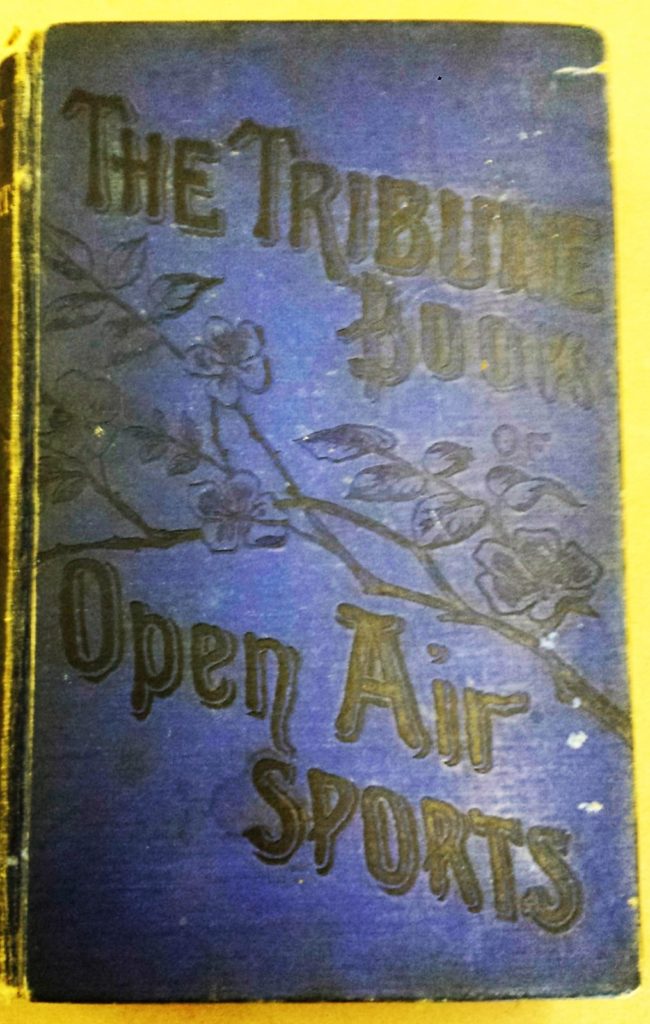

The New York Tribune was the first newspaper to use the Linotype machine, introduced with the July 3, 1886, issue. The first book printed by Linotype, was also begun that year and finished early 1887.

The New York Tribune was the first newspaper to use the Linotype machine, introduced with the July 3, 1886, issue. The first book printed by Linotype, was also begun that year and finished early 1887.

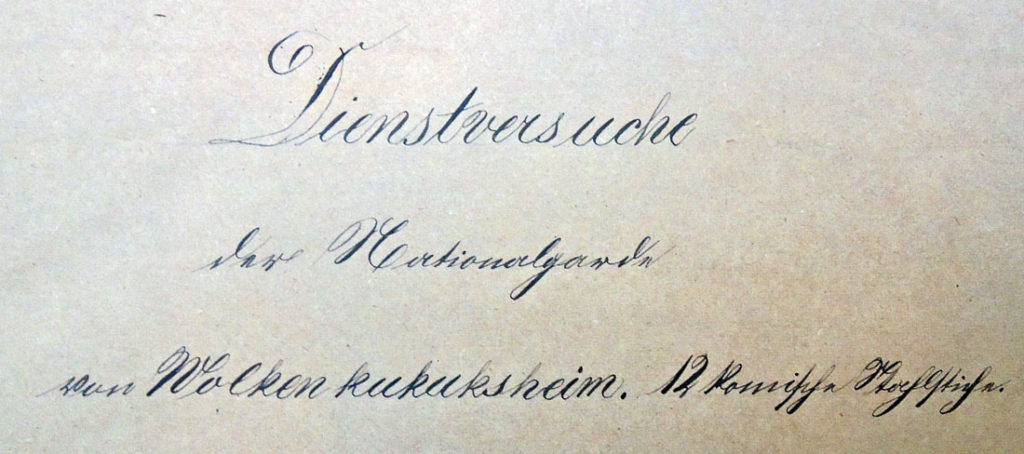

Henry Hall, editor, The Tribune Book of Open-Air Sports. Prepared by the New York tribune with the aid of acknowledged experts (New York: The Tribune Association, 1887). Formerly owned by Elmer Adler. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2004-1385N

Verso t.p.: “This book is printed without type, being the first product in book form of the Mergenthaler Machine which wholly supersedes the use of movable type.”

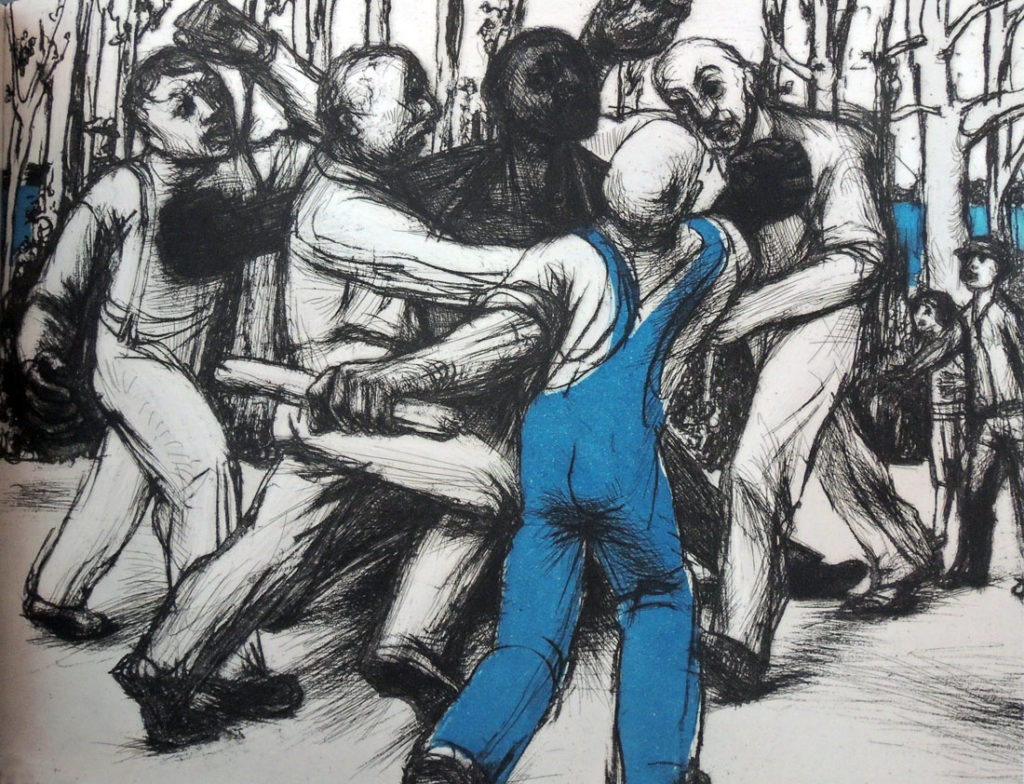

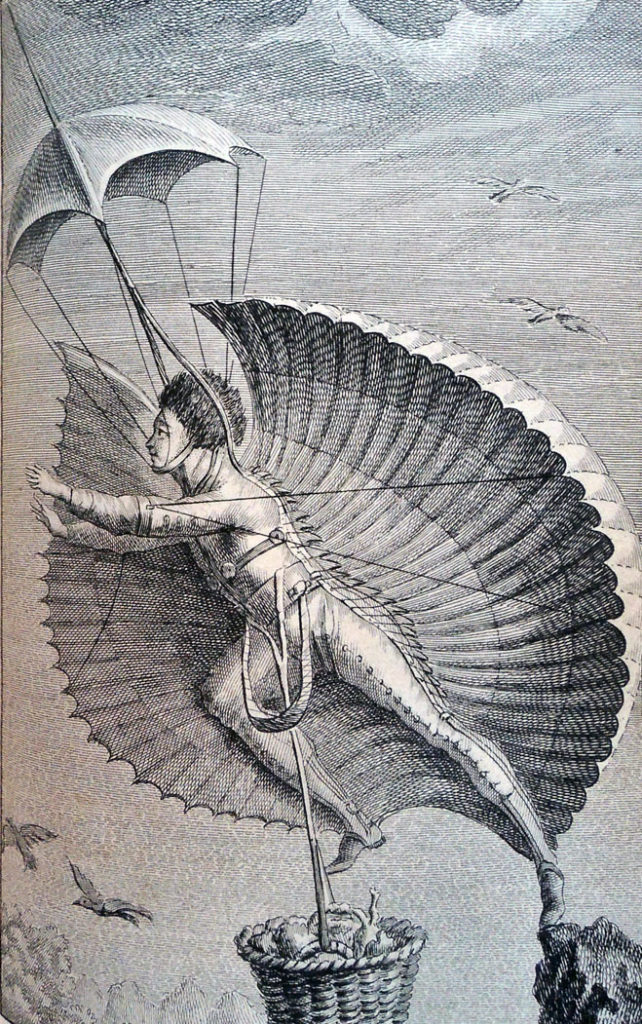

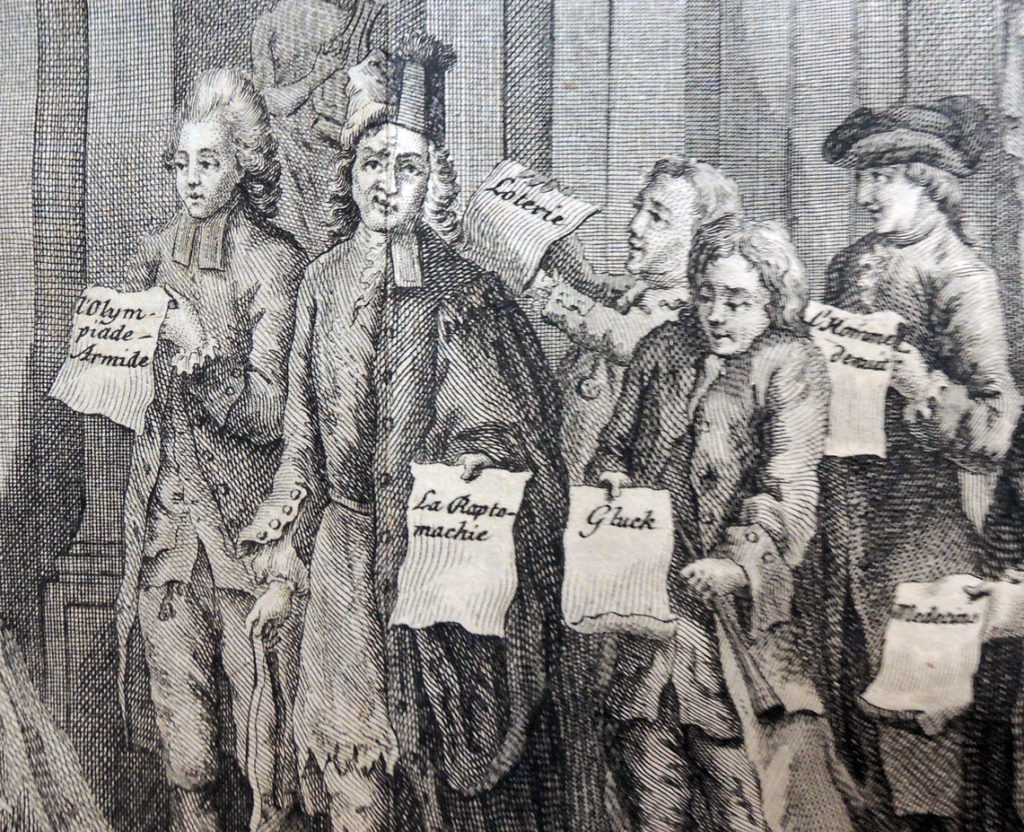

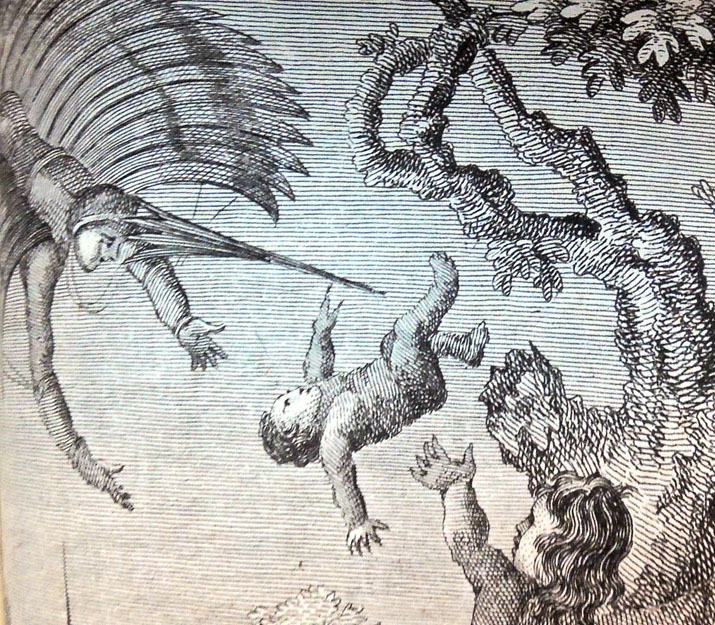

One of the books with type set on the Linotype machine at Woodside Press was: Shel Silverstein, Where the Sidewalk Ends (New York; Evanston; San Francisco; London: Harper and Row, c1974). Cotsen Children’s Library Eng 20 16941. Above is a plate from an updated edition.

One of the books with type set on the Linotype machine at Woodside Press was: Shel Silverstein, Where the Sidewalk Ends (New York; Evanston; San Francisco; London: Harper and Row, c1974). Cotsen Children’s Library Eng 20 16941. Above is a plate from an updated edition.

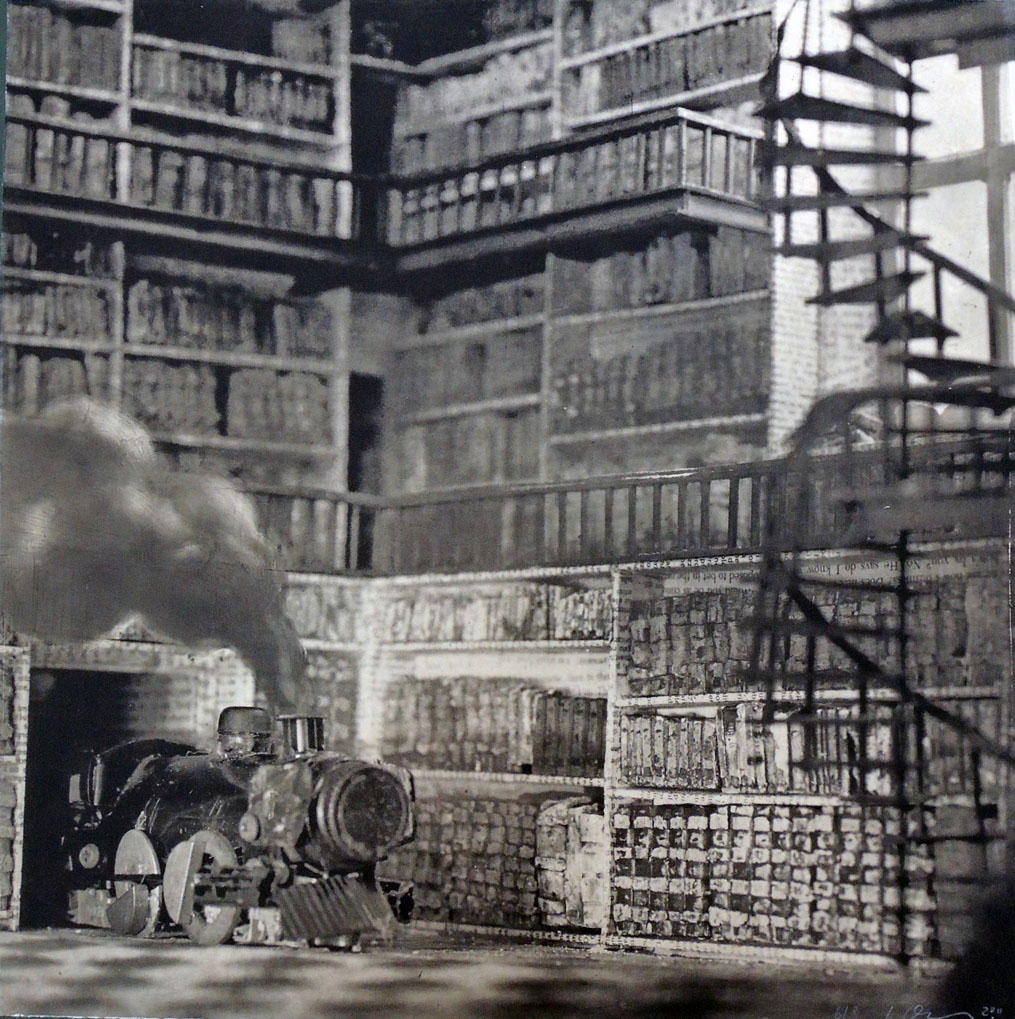

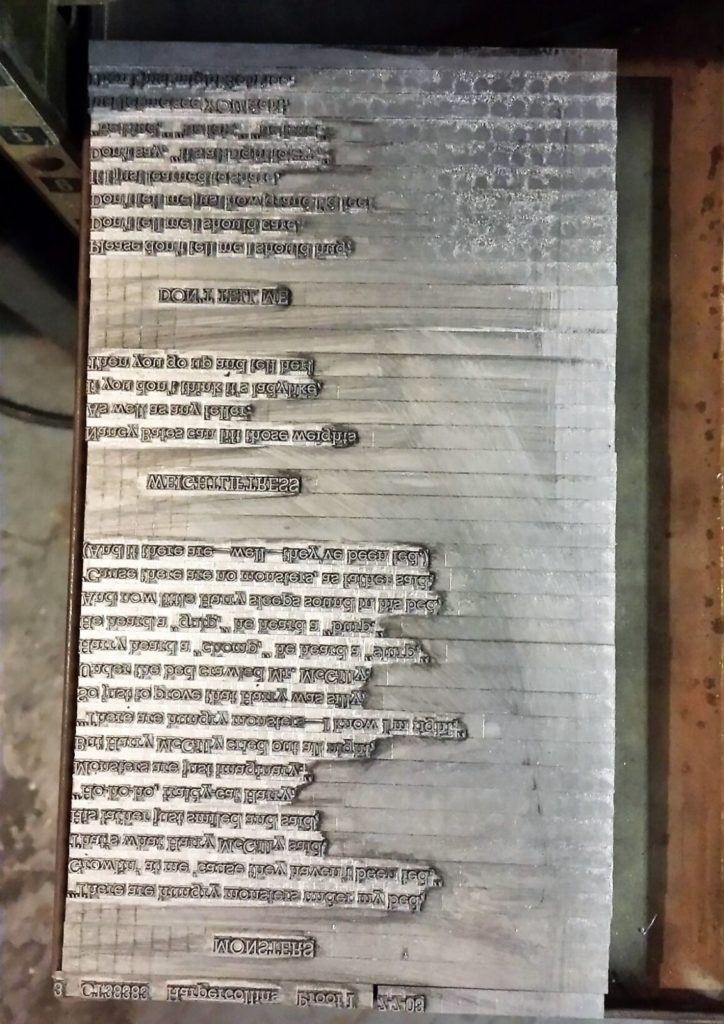

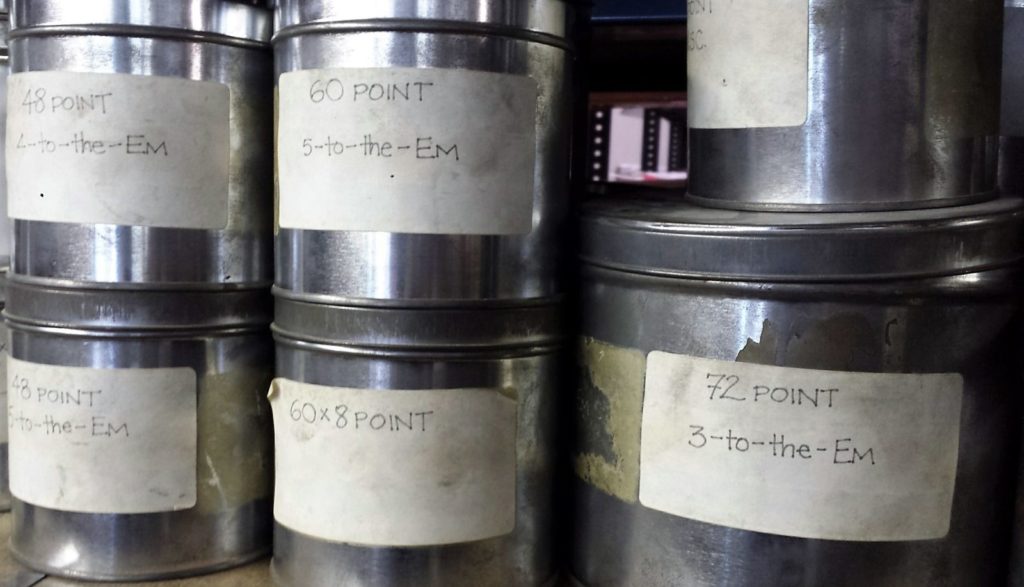

Shelves with dozens of EMs (empty spaces) housed by point size. Below cases of metal type.

Shelves with dozens of EMs (empty spaces) housed by point size. Below cases of metal type.