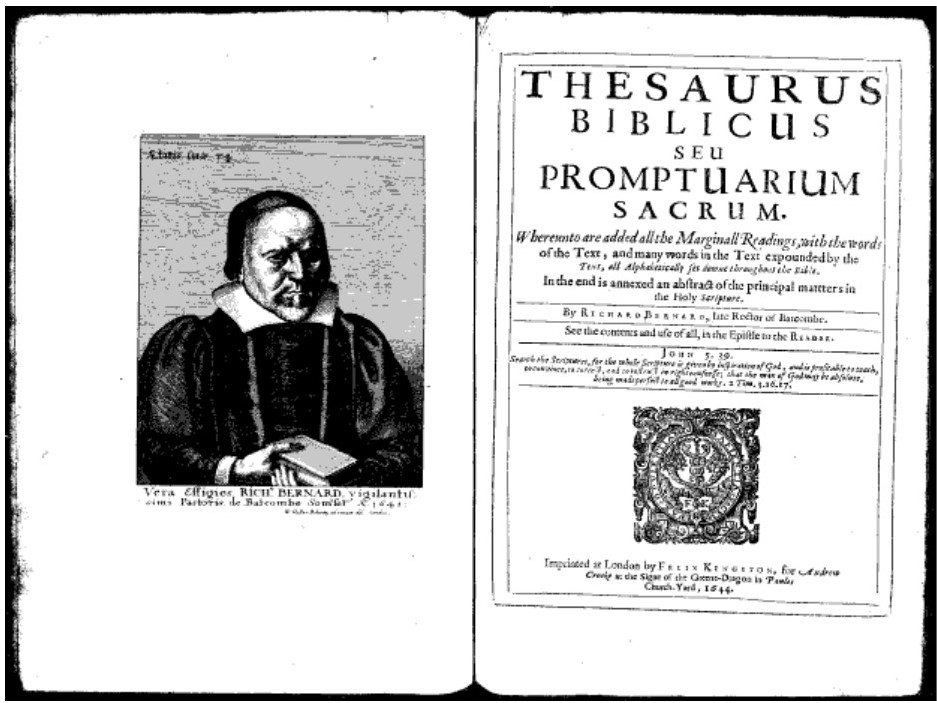

Back in April 2020, when we were all desperately searching for online resources to finish the semester’s work, we posted the British Museum’s portrait print by Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677), Vera Effigies, Rich. Bernard [Richard Bernard, 1568-1641], 1641. https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2020/04/02/the-legall-proceeding-in-man-shire-against-sinne/

Within a day a cheerful email appeared that began,

“Yesterday’s post about Richard Bernard with his portrait by W. Hollar especially caught my eye, as we have the etching, purchased at Walter Schatzki’s on 57th St. in October 1967 when I was a graduate student. We bought several prints from Schatzki around that time. Professor Koch had recommended him and his wonderful shop as a place for undergraduates to buy inexpensive but interesting works. We paid $6.67 for the print (the sheet of paper is 20.3 cm. high by 13.8 cm. wide), on sale for 1/3 off. Beyond my liking of the print as a work of art, I suppose I have thought Bernard might have resembled New England Puritans.”

With sincere thanks to William and Sally Rhoads (and to Walter Schatzki), that $6.67 etching is now in the Graphic Arts Collection, where it will certainly be used by a new generation of students and faculty.

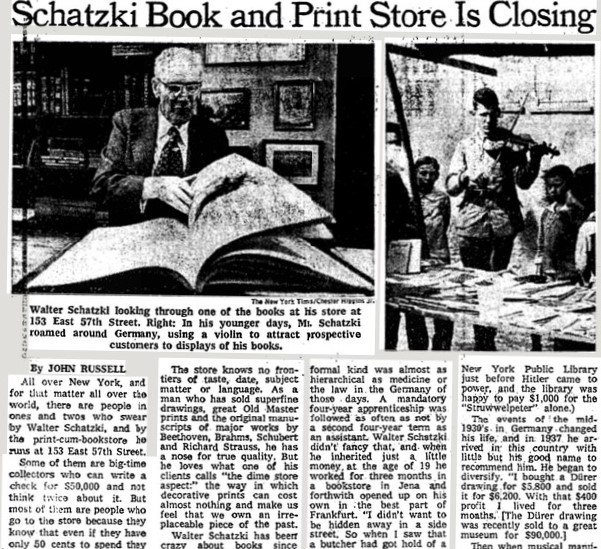

When Walter Schatzki’s Book and Print Shop closed in 1976, John Russell wrote a long article in the New York Times praising the dealer:

All over New York, and for that matter all over the world, there are people in ones and twos who swear by Walter Schatzki, and by the print‐cum‐bookstore he runs at 153 East 57th Street. Some of them are big‐time collectors who can write a check for 550,000 and not think twice about it. But most of them are people who go to the store because they know that even if they have only 50 cents to spend they can come away with something they like and be treated exactly as if they were Paul Mellon himself. All these enthusiasts—the experts and the beginners, the rich and the not so rich —have had bad news. On July 1 Mr. Schatzki is closing his store. “My lease is up,” he said the other day. ‘My rent would be almost tripled. I don’t feel like moving.

. . . Walter Schatzki has been crazy about books since 1910, when he hung around the bookstore in the town of Siegen, not far from Cologne, where he was born. And he has been in the business since 1919, when as a tall and very young man, already bespectacled, he went from village to isolated village in his native Germany with a violin in one hand, and a pack full of cheap good books on his back. “I went from fair to fair, and I would play my violin. People gathered round, and sometimes they sang a song or two, and then I opened my pack of books, and people would buy a book who had never seen a bookstore, let alone walked into.

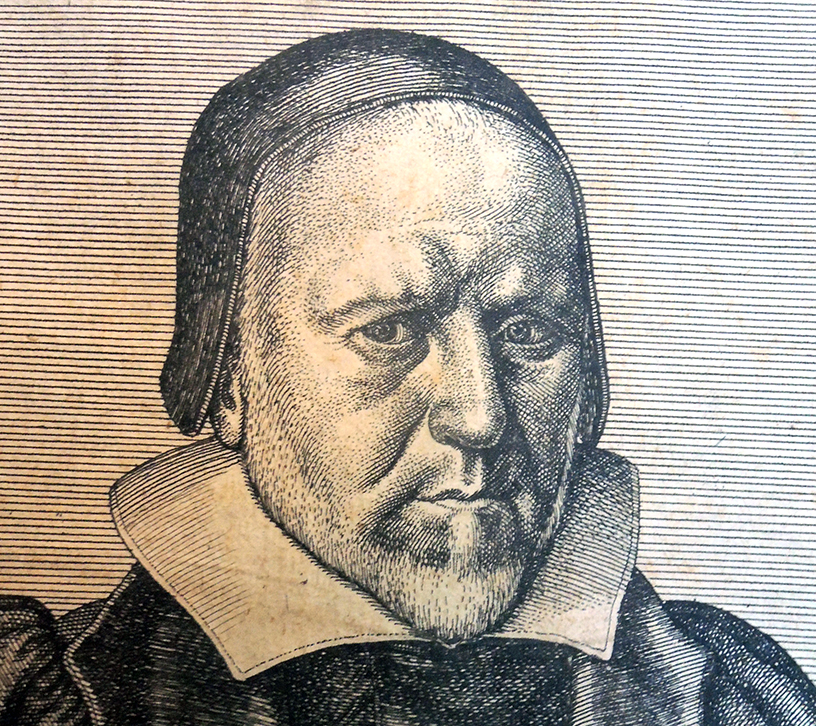

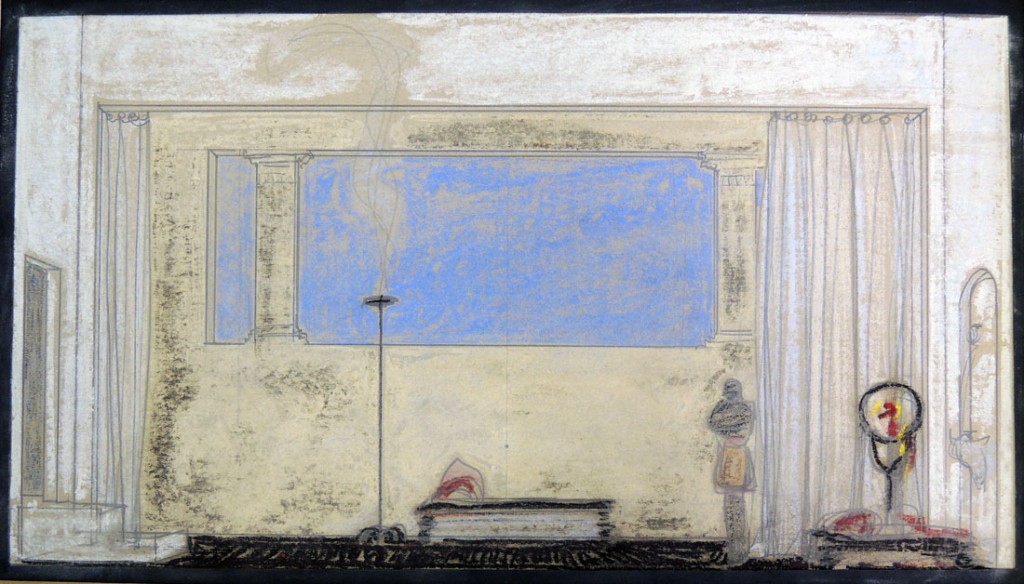

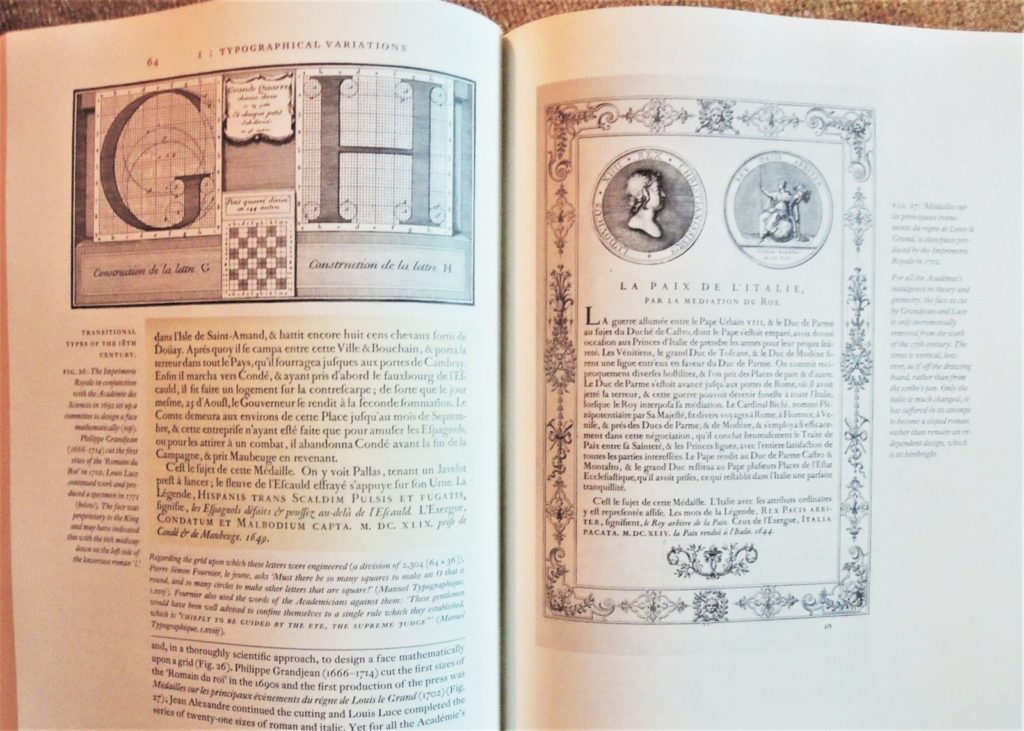

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677), Vera Effigies, Rich. Bernard [Richard Bernard, 1568-1641], 1641. Etching. Inscribed in the design, u.l., ‘Ætatis suæ 74’. Inscribed in the plate, l.l. to l.r., ‘Vera Effigies RICH. BERNARD vigilantis/ simi Pastoris de Batcombe Somrset: Ao; 1641’; l.c. to l.r., ‘W:Hollar. Bohem, ad viuum del: Londini:’ Gift of William and Sally Rhoads. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677), Vera Effigies, Rich. Bernard [Richard Bernard, 1568-1641], 1641. Etching. Inscribed in the design, u.l., ‘Ætatis suæ 74’. Inscribed in the plate, l.l. to l.r., ‘Vera Effigies RICH. BERNARD vigilantis/ simi Pastoris de Batcombe Somrset: Ao; 1641’; l.c. to l.r., ‘W:Hollar. Bohem, ad viuum del: Londini:’ Gift of William and Sally Rhoads. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process

Hollar’s 1641 print appears as a frontispiece in the subject’s 1644 book (and perhaps others):

Richard Bernard (1568-1641), Thesaurus Biblicus seu promptuarium sacrum, whereunto are added all the marginall readings, with the words of the text, and many words in the text expounded by the text, all alphabetically set downe throughout the Bible. In the end is annexed an abstract of the principal matters in the Holy Scripture (London: Imprinted by F. Kingston, 1644).

See:

Richard Pennington A Descriptive Catalogue of the Etched Work of Wenceslaus Hollar, 1607-1677. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1982, cat. no. 1363 only state.

Simon Turner Wenceslaus Hollar: New Hollstein German engravings, etchings and woodcuts, 1400-1700. Giulia Bartrum, vols. 1-9, 2009–2012, cat. no. 337 only state.